Pain neuroscience and evolutionary psychology tell us that if a person has pain they will most naturally want to avoid it or stop it. Historically, the treatment of pain leveraged the idea of sufficient pain control and depended on a direct relationship between an identifiable physical injury and a patient’s report of symptoms. The amount of pain was expected to be perfectly proportional to the amount of tissue or bodily damage “causing” the pain. Entire protocols, professions and medical centers have been built and constructed around the tightly held belief in the biomedical treatment of pain which assumes a one-to-one relationship between tissue damage, nociceptive input, and pain sensation.1 Unfortunately, this approach has not helped people with pain live vital lives. Instead, it has encouraged people to overly rely on pharmacologic therapy or invasive treatments that are often insufficient.2,3 In many cases it has further contributed to anxiety, depression, trauma, disability and suffering.4

Over the last century, this position was socially and culturally reinforced by our industrialized and financially incentivized medical-pharmaceutical system that continues to drive home the belief that pain is bad, people with pain are broken, they need to be fixed, and pain must be completely eliminated in order to achieve a sense of freedom and vitality. This is precisely where people living with pain struggle, become stuck and suffer. For too long, psychological or behavioral factors were thought to arise as a consequence of pain but not influence the pain itself. Important psychological factors were presumed to be contributors only in the rarest of cases where no identifiable pathology was present and the pain could be labeled as psychogenic.5

Thankfully, we have come a long way.

Today, the biomedical model has been replaced with a biopsychosocial model which incorporates all aspects of a person’s life that converge and potentially maintain pain. This is the paradigm shift from which all health care professionals are expected to evaluate and treat pain.6 This deep understanding leads the scientific community’s march for effective pain care and informs research, education, clinical practice and patient self-management. Pain care now openly embraces psychological, social, behavioral, and contextual factors, along with the biomedical.7 However, a gargantuan fissure separates this evidence-based knowledge from the skills and systems requisite to effectively apply treatment and obtain the best possible outcomes. In addition, the era of personalized medicine brings to the table the influence of epigenetic factors on behavior and human health.8 As practitioners, we can no longer ignore the interrelationship between neurobiological mechanisms and the psychological and social forces for optimizing individual patient outcomes. Life context matters and a method that takes all of this richness into account is desirable. Thanks to advances in new forms of cognitive behavioral therapy, practitioners have access to an evidence-based treatment to serve those living with pain. This treatment is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.9

Psychological Flexibility as a Foundational Aspect of Pain Care

A modern exploration of human suffering suggests chronic pain isn’t the enemy and that it doesn’t need to be stopped, eliminated or controlled to live a rich, meaningful and active life.10 Rather than focusing on changing physical or psychological pain directly, ACT seeks to change the function of those events and the individual’s relationship to them. Supported by research in Relational frame Theory, ACT informs us that psychological suffering is often caused by the interaction between language and cognition and its influence on human behavior.11,12 ACT targets the underlying processes of language and cognition that are hypothesized to be involved in suffering, its improvement and potentially its alleviation. While pain hurts, it is the psychological struggle with pain that causes humans to suffer. This makes an ACT approach to living with chronic pain altogether different and refreshing. It helps patients accept all types of unwanted and unpleasant inner experiences. There is no need to pump the breaks or overly manage pain to live fully. In many ways, ACT works to reverse the negative consequences that many people with pain have endured for years. Attempts to control pain can sometimes cause more harm than good, both to the body and to a person’s peace of mind.

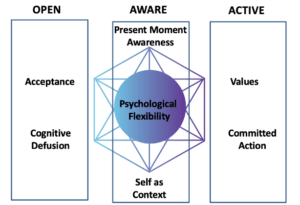

ACT uses acceptance, mindfulness, commitment, and behavior change strategies to improve vitality. As a process-based therapy13, six therapeutic processes all contribute to a positive psychological skill.

The six processes are:

- Acceptance

- Cognitive defusion

- Present moment awareness

- Self as context

- Values, and

- Committed action.14

Acceptance is the ability to actively embrace unwanted private experiences, including pain, thoughts, feelings, and memories, without attempting to change their frequency or form. Acceptance is not a passive process, nor does it imply giving in to pain, resignation, or tolerance. This is an active and open posture of curiosity and interest in our feelings, memories, bodily sensations, and thoughts. The goal is not to reduce symptoms but to increase how we respond to the presence of these behavior narrowing experiences.

Cognitive defusion is the ability to see thoughts as what they are, not as what they say they are. Thoughts can often have a literal quality to them. ACT uses cognitive defusion to change the way one interacts with thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations. Cognitive defusion and mindfulness techniques are used to create more flexibility in the presence of challenging thoughts by bringing awareness to the process of ongoing thinking.

Present moment awareness actively focuses on experiences as they are occurring now, in the moment, in real-time. Attention to pain can pull you into the past or future and exacerbate rumination, catastrophizing, and worry. This makes pain worse. Attention focused and mindfulness exercises are used to train a flexible present moment awareness.

Self as context or the “observer self” helps patients to notice a distinction between observed thoughts and the person who observes. This perspective provides a safe psychological space for facing painful feelings or thoughts. It also helps understand the perspective of others and promotes prosocial behavior. A self as context act is fostered by mindfulness, metaphors, and perspective-taking exercises.

Values are unique to ACT. They rev up behavior change and maintain motivation. ACT encourages the clarification of cloudy values and the full exploration of personally held values. ACT uses metaphors, experiential exercises, self-exploration, and writing exercises as ways to clarify values.

Committed action is about choosing a course of action guided by personally held values. ACT encourages the development of larger and larger patterns of action linked to chosen values. In this regard, ACT looks very much like many other approaches including exposure, skills training, and goal setting. Values-consistent goals are encouraged and can be broken down into goals that are SMART: Specific, Meaningful, Adaptive, Realistic, and Time-framed.

These six processes can be folded into three and describe a behavior that is open, aware, and active. Open includes the two processes (acceptance and cognitive defusion), Aware (present moment awareness and self as context), and Active (values and committed action). The six core processes and three components are commonly organized in what is referred to as the ACT hexaflex (see figure 1). These are at work in ACTs metaphors, stories, and exercises, although not explicitly mentioned to alleviate confusion and overly technical jargon. ACT is not a didactic or an overly instructive approach, and avoids lengthy explanations. It is an experiential therapy and thus includes exercises requiring contact with your body, mind, and heart. Upon first glance, it might be assumed that as a therapist you zoom in and target a specific process with a specific exercise (today I’m targeting cognitive defusion with mindfulness). The beauty of the ACT model is it is an interconnected system. As you strum one process you tune them all.

Figure 1. ACT Hexaflex

At the core of ACT is psychological flexibility. Psychological flexibility can be defined as contacting the present moment as a conscious human being, fully and without defense, as it is and not as it says it is and persisting or changing in behavior in the service of chosen values. All six processes are interconnected, work together, and contribute to training psychological flexibility. With the development of greater psychological flexibility, even people with the most retractable pain are able to move toward better health and a rich, meaningful, and active life.15, 16 Along for the ride are our thoughts, feelings, memories, and sensations, both pleasant and unpleasant. Psychological flexibility increases the repertoire of available reactions to pain. People consciously choose to act in ways that support values and re-engage with life.

How ACT Differs from Traditional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or Pain Education

People living with pain experience many types of thoughts, feelings, memories, and physical sensations. These experiences can be pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. They may influence a person to avoid, eliminate, struggle, or make attempts to change them. People with pain reduce their activity, engage in excessive thoughts about pain, ruminate about the cause of pain, visit multiple practitioners, overmedicate, and find ways to distract. The ever-expanding behaviors that develop in an effort to control pain squeezes out the joy and human potential. This persistent focus on pain control narrows life and is harmful to wellbeing. Trying to persistently rid oneself of painful sensations, unwanted emotions, distressing memories or unpleasant thoughts leads one away from their personally chosen values— the activities that are desired and meaningful. This experiential avoidance contributes to psychological inflexibility and causes suffering.17

In many ways, ACT challenges conventional methods of pain management that focus on pain control and symptom reduction. At times, it may feel different than traditional cognitive behavioral therapy or the more recent pain education approaches. These cognitive-behavioral therapies aim to change pain-related cognitions, challenge pain-related beliefs, restructure thoughts, provide education where it is lacking, and uses motivational incentives to reduce fear, pain, and other symptoms.18 The suggestion is that when fear and pain-related thoughts are reduced, the patient no longer needs to avoid a situation and can behave more effectively. This approach has been acknowledged as one of the safest and most effective treatment approaches for chronic pain.19 Indeed, traditional cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain has been successful in many ways. Yet traditional cognitive-behavioral approaches for pain report small benefits for disability, mood, and catastrophic thinking in trials that compared cognitive behavioral therapy with no treatment, and long-term benefits often wane.20 Similarly, modern pain education approaches purport to assist patients to reconceptualize their pain away from a biomedical cause and towards a more biopsychosocial understanding.21 This approach aims to change or modify thoughts and beliefs about the cause of pain and has added to our cognitive methods of treating pain. However, varying degrees of reconceptualization exist with most patients showing only partial reconceptualization.22 Our ability to change pain-related thoughts and beliefs is often patchy, and people are left suffering. Even though a 2019 meta-analysis in the Journal of Pain reported that pain education helps people cope, investigators found it does not produce clinically significant decreases in pain or disability.23 Further methods to help people with both their inner experiences related to thoughts, feelings, and sensations as well as their outer world behavior is desirable.

ACT shows us that emotional responses such as fear, pain-related thoughts, and memories from a person’s unique learning history cannot be changed nor completely eliminated. There is no replacement cartridge or delete button in the nervous system to erase and rewrite what’s been learned. The strong possibility remains that some life events will occur in the future where these same feelings and thoughts yet again influence behavior and may very likely remain, at least to some extent for the people we care for. ACT does not attempt to change thoughts or beliefs and it is not pain relief focused. Although pain relief may occur, it is not an absolute prerequisite for vital living. Clinically, there is minimal interest in what is true or false about pain in any sense (e.g., when clients struggle to determine whether their thoughts or beliefs about their back pain is or is not caused by a herniated disc). Instead, there is a great interest in workability (e.g., how is it working for the individual to struggle to determine whether his or her thoughts or beliefs about back pain are correct?) It can be difficult to think or talk oneself out of a situation created by thinking and talking. Education, logic, and instruction may have limits in cultivating the processes of behavior change.

In general, the difference between traditional cognitive-behavioral therapies and ACT lies in the contextual philosophy.24 The underpinnings of a functional contextual approach with its unique theory of language and cognition leads to a treatment model of chronic pain that is exposure-based, but looks very different than traditional cognitive behavioral therapy. The evidence for pain exposure specifically is good and continues to grow in the pain science literature.25 Exposure to pain-related fear, thoughts, anxiety, or pain itself are useful parts of any approach. Pain exposure is often trained in practice as graded exposure or graded activity. 26 This hierarchical approach uses mild exposure and repeated events to a feared movement, exercise or activity. Employed by physical therapists, occupational therapists, and psychologists, the focus is on increasing the capacity in a step-by-step, graded, and pain-contingent manner. The aim with these techniques was habituation defined as a decrease in arousal or extinction of fear responses that occurs after repetition of a task. This theory prefaced that repeated exposure to a feared event will reduce pain that is associated with an event. As an ACT practitioner, Radical Relief will help you develop a different and updated approach to exposure since a reduction of symptoms or discomfort is not high on the list of clinical goals. Although exposure is often an ingredient in traditional cognitive behavior therapies, the objective or function in ACT is different. Rather than altering responses through extinction or habituation, the primary objective is to train specific psychological processes such as acceptance and defusion.27 This facilitates the development of a more flexible behavior in the presence of pain and distress, and engagement in activities that bring meaning and vitality into one’s life. Exposure therapy guided by ACT creates new learning and new ways of relating.28 This is achieved through experiential exercises, the metaphorical use of language, methods designed to undermine the entanglement of thoughts and private experiences rather than merely to change them. Exposure is best used to teach vital actions that can be taken both when it feels good and certain as well as when fear and pain are present or even when our thoughts say it cannot be achieved. The best research after years of investigation informs us that treatments that include one small component of pain education and one predominant component of exposure therapy are able to produce large effect sizes in chronic pain.29 Radical Relief applies the evidence and proposes a framework combining pain education and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. The first three chapters take a pain education approach. The remaining chapters and bulk of the book swiftly change to exposure and training the processes of psychological flexibility.

The other big difference in the ACT approach is in the contextual framework, including the mindfulness approach.30 Clients using ACT, as opposed to traditional cognitive-behavioral therapies, discover, clarify, and reconnect to their own values, which changes the context and serves as the motivation for behavior change.31 In the ACT approach, positive reinforcement or what can be looked upon vital living is identified through the use of values and certain mindfulness exercises. In this way, one’s values provide the motivation for the client to develop and maintain the willingness to make the changes that are needed to get life back on track. This empowers the individual to access their own resources for overcoming pain.

Finally, the cornerstone of ACT is the concept of workability. Here you work with the patient to help them examine the workability of the strategies they are using. We ask the question; have the strategies the person is using to live their life or solve their problems worked? An ACT therapist asks, “Is what you’re doing working to give you a rich, meaningful, and active life?” If the answer is yes, the behavior is workable. To an ACT therapist, thinking, feeling, and remembering are all considered behaviors because they are all things a person does. If the answer is no, it’s unworkable, in which case we consider alternatives that better serve valued living. In other words, we want to know if a thought, belief, memory, or sensation helps a patient move toward a richer, more meaningful, and active life. To determine this, we may ask questions like these: “If you let this thought guide your behavior, will that help you create a richer, more meaningful, and active life? If you hold on to this thought tightly, does it help you to be the person you want to be and do the things you want to do?” For example: if we find patients are fused with thoughts and beliefs about themselves then we turn to processes such as defusion, acceptance, and make contact with the unworkability of their strategies and the unhelpfulness of “overthinking” and of buying into thoughts. This means that each behavior is evaluated on the basis of whether or not it is improving or limiting one’s quality of life.

ACT and the Therapeutic Relationship

No matter how advanced our methods become, the relationship between patient and clinician is of critical importance. In ACT, we hold the therapeutic relationship as an important component of the therapeutic process and its contextual behavioral approach provides a clearer understanding of the impact of the therapeutic relationship on patient outcomes.32 ACT is unique in that it is not solely based on the premise of abnormal thinking or maladaptive beliefs about pain.33 The client, or their thoughts, are never viewed as incorrect, broken, damaged, or beyond hope. Instead, the stance is always one of empowerment; that a rich, meaningful, values-based life is within reach for us all. Pain is taken to be part of life, not an enemy to be stopped. Progress in therapy is not defined by a list of short- and long-term goals that are progressively checked off in succession but rather by the choice to embrace the present and to step forward toward a life worth living. Consider for a moment that there may be more courage and vitality in a person struggling with pain choosing to go to a gentle yoga class than there is for a quarterback training for the Super Bowl.

The therapeutic stance in ACT is one of human equality. The therapist and the patient are both human beings who have minds. They are both humans who have at times had struggles, heartache, joy, sadness, longing, and hurt. The therapeutic relationship differs from traditional cognitive behavioral therapy or pain education in that the client is regarded as fully competent and able to take charge of his or her own recovery. This, in turn, creates a different therapeutic bond. For example, when acceptance, mindfulness, and exposure are used in traditional cognitive therapy they are generally used along with a variety of other techniques linked to the hope that pain will decrease or be better managed. Conversely, in ACT acceptance, mindfulness, and exposure are never linked to pain management, reduction, or control. Instead, they are methods of enhancing a vital life. The ACT therapist is active and values-oriented, though if the goal is to be better able to willingly be with painful sensations, the therapist may sit quietly, empathizing, providing gentle encouragement, and allowing space for emotion to be present while helping the patient cultivate an accepting, flexible, defused and present awareness towards that which is unpleasant. In sum, ACT differs from traditional cognitive behavioral therapy in its focus on moving toward a vital life rather than on pain management. It should be noted that a response to suffering and the ordeal that it causes patients calls for practitioners to cultivate the same psychological skills as our patients. This work calls for us, practitioners, to be open, aware, engaged, present, defused, and psychologically flexible. We are partaking in the same process and journey. Being present is indeed the most challenging aspect of healing for the courage it requires. Putting these ideas together implies that a practitioner is willing to accompany a patient on a journey into vulnerable spaces to confront the demons of fear, the emptiness of loss, red hot anger that might arise, profound sadness, and the isolation that causes suffering. This journey is not routine, but emotional, unpredictable, and uniquely human. Such a relationship offers the patient the possibility of finding a new sense of hope, balance, integrity and wholeness with a new meaning for life.

Dr. Tatta’s simple and effective pain assessment tools. Quickly and easily assess pain so you can develop actionable solutions in less time.

Infusing ACT into Physical Therapy and Other Health Professions

ACT has been shown to have positive effects on chronic pain and meta-analyses show improvements in depression, anxiety, pain intensity, pain interference, physical functioning, and quality of life. 34,35,36 This has made it attractive for mental health and physical medicine professionals alike. A wide variety of health professionals can use ACT to inform their treatment of pain and it cuts across specialties. This includes physical therapists, occupational therapists, nurses, physicians, health coaches, and of course, mental health professionals.

Physical therapy is often the first point of entry into the healthcare system for people experiencing pain. The non-invasive and non-pharmacologic approach taken by physical therapists towards the treatment of pain makes the profession ideally suited to adopt evidence-based therapies of psychologically-informed practice. Treatments based on principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy, including acceptance and commitment therapy, delivered by professionals other than psychologist continue to flourish and show promise.37,38,39 Within a self-management approach, physical therapists can weave principles of ACT into practice and effectively addresses the psychological distress associated with chronic pain. 40

The incorporation of cognitive-behavioral techniques such as ACT into the praxis of physical therapy allows professionals to apply a biopsychosocial approach to pain rehabilitation.41 A physical therapist with proper training can deliver ACT with high fidelity and successfully reduce disability.42 Radical Relief provides foundational skills to implement it into physical therapist practice. This has been shown to further one’s understanding of the psychological factors associated with pain, increased one’s confidence level in managing musculoskeletal pain, and with sufficient training and supervision leads to improved job satisfaction.43

With sufficient training and ongoing mentorship, physical therapists and other health professionals can implement ACT alongside other types of therapies, including pain education and exercise therapy.44 It can be used face-to-face, via telehealth, in individual or group programs. Professionals can choose from brief time-limited interventions for busy primary musculoskeletal practice or implement full protocols guided by the core processes. Across a wide range of conditions, practitioners, and practice settings, ACT seeks a unified model of behavior change.45

ACT as an Experiential Approach to Behavior Change

Across a wide range of conditions, practitioners, and practice settings, ACT seeks a unified model of behavior change.45 Keep in mind that ACT is a process-based, experiential therapy. This is different than talking about or explaining pain and does not prescribe a protocol instructing you to use one technique before another. An ACT therapist not only understands the concepts and can recite the exercises but, most importantly, embody the model in life. As you learn ACT, you will notice where you may be stuck, where avoidance dominates, and acceptance is required. You will cultivate mindfulness skills and notice the content of your thoughts more readily. Your behavior will change, and motivation will be sustained as you contact your own values and commit to new ways of living. Training in ACT for professionals has led to significant behavioral and self-care changes linked to the core processes of psychological flexibility.46 As your competency increases, so too, will your psychological flexibility and stance as a practitioner.47 The stance of the ACT therapist is an especially important factor in providing care. Therapists come to ACT from all different professions and with a variety of skills and knowledge. How best to learn ACT has not been well studied although experts agree that an intensive educational training with monthly supervision is ideal. 48

Would you like to learn more about ACT for Chronic Pain?

Here are three additional resources:

References:

1. Bendelow G. (2013). Chronic pain patients and the biomedical model of pain. The virtual mentor : VM, 15(5), 455–459. https://doi.org/10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.5.msoc1-1305.

2. Hylands-White, N., Duarte, R. V., & Raphael, J. H. (2017). An overview of treatment approaches for chronic pain management. Rheumatology international, 37(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-016-3481-8.

3. Jonas, W. B., Crawford, C., Colloca, L., Kriston, L., Linde, K., Moseley, B., & Meissner, K. (2019). Are Invasive Procedures Effective for Chronic Pain? A Systematic Review. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.), 20(7), 1281–1293. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pny154.

4. Sullivan M. D. (2018). Depression Effects on Long-term Prescription Opioid Use, Abuse, and Addiction. The Clinical journal of pain, 34(9), 878–884. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000603.

5. Meints, S. M., & Edwards, R. R. (2018). Evaluating psychosocial contributions to chronic pain outcomes. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry, 87(Pt B), 168–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.01.017.

6. Darnall, B. D., Carr, D. B., & Schatman, M. E. (2017). Pain Psychology and the Biopsychosocial Model of Pain Treatment: Ethical Imperatives and Social Responsibility. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.), 18(8), 1413–1415. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnw166.

7. Edwards, R. R., Dworkin, R. H., Sullivan, M. D., Turk, D. C., & Wasan, A. D. (2016). The Role of Psychosocial Processes in the Development and Maintenance of Chronic Pain. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society, 17(9 Suppl), T70–T92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2016.01.001.

8. Mohamad M. Kronfol, Mikhail G. Dozmorov, Rong Huang, Patricia W. Slattum & Joseph L. McClay (2017) The role of epigenomics in personalized medicine, Expert Review of Precision Medicine and Drug Development, 2:1, 33-45, DOI: 10.1080/23808993.2017.1284557.

9. Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

10.Vowles, K. E., Witkiewitz, K., Levell, J., Sowden, G., & Ashworth, J. (2017). Are reductions in pain intensity and pain-related distress necessary? An analysis of within-treatment change trajectories in relation to improved functioning following interdisciplinary acceptance and commitment therapy for adults with chronic pain. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 85(2), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000159.

11. Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Roche, B. (Eds.). (2001). Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York: Plenum Press.

12. Wicksell, R. K., & Vowles, K. E. (2015). The role and function of acceptance and commitment therapy and behavioral flexibility in pain management. Pain Management, 5(5), 319-322. doi:10.2217/pmt.15.32.

13. Hayes, S. C., Hofmann, S. G., Stanton, C. E., Carpenter, J. K., Sanford, B. T., Curtiss, J. E., & Ciarrochi, J. (2019). The role of the individual in the coming era of process‐based therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 117, 40– 53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.10.005.

14. Feliu-Soler A, Montesinos F, Gutiérrez-Martínez O, Scott W, McCracken LM, Luciano JV. Current status of acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a narrative review. J Pain Res. 2018;11:2145-2159 https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S144631.

15. McCracken, L. M., & Gutiérrez-Martínez, O. (2011). Processes of change in psychological flexibility in an interdisciplinary group-based treatment for chronic pain based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(4), 267-274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.02.004.

16. A-Tjak, J. G. L., Davis, M. L., Morina, N., Powers, M. B., Smits, J. A. J., & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2015). A Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Clinically Relevant Mental and Physical Health Problems. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(1), 30-36. doi:10.1159/000365764.

17. Gentili, C., Rickardsson, J., Zetterqvist, V., Simons, L. E., Lekander, M., & Wicksell, R. K. (2019). Psychological Flexibility as a Resilience Factor in Individuals With Chronic Pain. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 2016. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02016.

18. Sturgeon J. A. (2014). Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain. Psychology research and behavior management, 7, 115–124. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S44762

19. Ehde, D. M., Dillworth, T. M., & Turner, J. A. (2014). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. The American psychologist, 69(2), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035747.

20. Williams, A., Eccleston, C., & Morley, S. (2012). Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(11). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub3.

21. Moseley, L. (2007). Reconceptualising pain according to modern pain science. Physical Therapy Reviews, 12, 169-178. doi:10.1179/108331907X223010.

22. King, R., Robinson, V., Ryan, C. G., & Martin, D. J. (2016). An exploration of the extent and nature of reconceptualisation of pain following pain neurophysiology education: A qualitative study of experiences of people with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Patient education and counseling, 99(8), 1389–1393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.03.008.

23. King, R., Robinson, V., Elliott-Button, H. L., Watson, J. A., Ryan, C. G., & Martin, D. J. (2018). Pain Reconceptualisation after Pain Neurophysiology Education in Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Qualitative Study. Pain research & management, 2018, 3745651. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3745651.

24. Watson, J. A., Ryan, C. G., Cooper, L., Ellington, D., Whittle, R., Lavender, M., Dixon, J., Atkinson, G., Cooper, K., & Martin, D. J. (2019). Pain Neuroscience Education for Adults With Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society, 20(10), 1140.e1–1140.e22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2019.02.011.

25. Hayes, S. C., Levin, M. E., Plumb-Vilardaga, J., Villatte, J. L., & Pistorello, J. (2013). Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behavior therapy, 44(2), 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2009.08.002.

26. Glombiewski, J. A., Holzapfel, S., Riecke, J., Vlaeyen, J. W. S., de Jong, J., Lemmer, G., & Rief, W. (2018). Exposure and CBT for chronic back pain: An RCT on differential efficacy and optimal length of treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(6), 533–545. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000298.

27. Macedo, L. G., Smeets, R. J. E. M., Maher, C. G., Latimer, J., & McAuley, J. H. (2010). Graded Activity and Graded Exposure for Persistent Nonspecific Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review. Physical Therapy, 90(6), 860-879. doi:10.2522/ptj.20090303.

28. Craske, M. G., Treanor, M., Conway, C. C., Zbozinek, T., & Vervliet, B. (2014). Maximizing exposure therapy: an inhibitory learning approach. Behaviour research and therapy, 58, 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006.

29. McCracken, L.M. (2020), Necessary components of psychological treatment for chronic pain: More packages for groups or process‐based therapy for individuals?. Eur J Pain, 24: 1001-1002. doi:10.1002/ejp.1568.

30. Coletti, J. P., & Teti, G. L. (2015). Terapia de Aceptación y Compromiso (ACT): conductismo, mindfulness y valores [Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): Behaviorism, mindfulness and values]. Vertex (Buenos Aires, Argentina), XXVI(119), 37–42.

31. Vowles, K. E., Sowden, G., Hickman, J., & Ashworth, J. (2019). An analysis of within-treatment change trajectories in valued activity in relation to treatment outcomes following interdisciplinary Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for adults with chronic pain. Behaviour research and therapy, 115, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.10.01

32. Vilardaga, R., & Hayes, S. (2009). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and the Therapeutic Relationship Stance. European Psychotherapy, 9, 117-140.

33. Bunzli, S., Smith, A., Schütze, R., Lin, I., & O’Sullivan, P. (2017). Making Sense of Low Back Pain and Pain-Related Fear. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy, 47(9), 628–636. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2017.7434.

34. Hughes, L. S., Clark, J., Colclough, J. A., Dale, E., & McMillan, D. (2017). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. The Clinical journal of pain, 33(6), 552–568. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000425

35. Veehof, M. M., Trompetter, H. R., Bohlmeijer, E. T., & Schreurs, K. M. (2016). Acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a meta-analytic review. Cognitive behaviour therapy, 45(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2015.1098724.

36. Vowles, K. E., Pielech, M., Edwards, K. A., McEntee, M. L., & Bailey, R. W. (2019). A Comparative Meta-Analysis of Unidisciplinary Psychology and Interdisciplinary Treatment Outcomes Following Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Adults with Chronic Pain. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society, S1526-5900(19)30841-7. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2019.10.004.

37. Barker, K. L., Heelas, L., & Toye, F. (2016). Introducing Acceptance and Commitment Therapy to a physiotherapy-led pain rehabilitation programme: an Action Research study. British Journal of Pain, 10(1), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463715587117.

38. Hall, A., Richmond, H., Copsey, B., Hansen, Z., Williamson, E., Jones, G., Fordham, B., Cooper, Z., & Lamb, S. (2018). Physiotherapist-delivered cognitive-behavioural interventions are effective for low back pain, but can they be replicated in clinical practice? A systematic review. Disability and rehabilitation, 40(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1236155.

39. Silva Guerrero AV, Maujean A, Campbell L, Sterling M. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Psychological Interventions Delivered by Physiotherapists on Pain, Disability and Psychological Outcomes in Musculoskeletal Pain Conditions. Clin J Pain. 2018;34(9):838-857. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000601.

40. Hutting, N., Johnston, V., Staal, J. B., & Heerkens, Y. F. (2019). Promoting the Use of Self-management Strategies for People With Persistent Musculoskeletal Disorders: The Role of Physical Therapists. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy, 49(4), 212–215.

41. Holopainen, R., Simpson, P., Piirainen, A., Karppinen, J., Schütze, R., Smith, A., OʼSullivan, P., & Kent, P. (2020). Physiotherapists’ perceptions of learning and implementing a biopsychosocial intervention to treat musculoskeletal pain conditions: a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Pain, 161(6), 1150–1168. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001809.

42. Godfrey, E., Wileman, V., Galea Holmes, M., McCracken, L. M., Norton, S., Moss-Morris, R., Noonan, S., Barcellona, M., & Critchley, D. (2019). Physical Therapy Informed by Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (PACT) Versus Usual Care Physical Therapy for Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society, S1526-5900(19)30065-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2019.05.012.

43. Tatta, J. (2020) Physical Therapists’ Perceptions of Learning and Implementing Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Chronic Pain: A Pilot Study on the Integrative Pain Science Institute Experience. New York, NY: Integrative Pain Science Institute. Retrieved from: www.integrativepainscienceinstitute.com/physical-therapists-perceptions-of-learning-and-implementing-acceptance-and-commitment-therapy-act-to-treat-chronic-pain-a-pilot-study-on-the-integrative-pain-science-institute-experience/

44. Casey, M. B., Smart, K., Segurado, R., Hearty, C., Gopal, H., Lowry, D., Flanagan, D., McCracken, L., & Doody, C. (2018). Exercise combined with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ExACT) compared to a supervised exercise programme for adults with chronic pain: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials, 19(1), 194. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2543-5.

45. Hayes S. C. (2019). Acceptance and commitment therapy: towards a unified model of behavior change. World psychiatry: official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 18(2), 226–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20626.

46. Pakenham, K. I. (2015). Investigation of the utility of the acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) framework for fostering self-care in clinical psychology trainees. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 9(2), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000074.

47. Walser, R. D., Karlin, B. E., Trockel, M., Mazina, B., & Barr Taylor, C. (2013). Training in and implementation of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for depression in the Veterans Health Administration: therapist and patient outcomes. Behaviour research and therapy, 51(9), 555–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.009.

48. Walser, R. D., O’Connell, M., Coulter, C.(2019) The Heart of ACT: Developing a Flexible, Process-Based, and Client-Centered Practice Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Context Press.