Chronic pain presents a physical and psychological burden for millions of Americans, and is a global health pandemic. This burden has been worsened by the widespread emphasis placed on a biomedical approach that largely neglects to address the psychosocial components and processes of chronic pain. This omission has led to poorly managed pain, the chronification of pain, and the misuse of pharmaceutical medications and invasive procedures (1). Research has shown that the main predictors of pain chronification (i.e. the process by which acute pain becomes chronic), are social and psychological factors, rather than purely biomedical. (2, 3). If not properly addressed, these factors negatively impact pain treatment, decrease the efficacy of interventions, and are related to poor functional outcomes and quality of life. This highlights the urgent need for comprehensive pain management approaches that address biomedical factors along with cognitive and behavioral obstacles to pain rehabilitation efforts.

Physical therapy is often the first point of entry into the healthcare system for people experiencing pain. The non-invasive and non-pharmacologic approach taken by physical therapists towards the treatment of pain makes the professional ideally suited to adopt evidence-backed technologies of psychologically-informed pain care traditionally neglected by standard biomedical treatments. Indeed, physical therapists are now expected to recognize pain associated with psychosocial distress (yellow flags) and to modify their treatment approach accordingly (4, 5, 6). However, available studies have indicated that the psychological aspects of pain are insufficiently addressed in entry-level physical therapy education programs and current clinical practice settings (7). Results of a 2015 nationwide survey that evaluated the extent of pain education in entry-level physical therapist education programs revealed that only 2.7 contact hours on average were devoted to psychological management of pain (8).

Mounting evidence suggests that incorporating principles of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), including Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), into standard physical therapy treatments can be effective and address the psychological distress associated with chronic pain (9, 10). ACT (said as one word) is a process-based, third-wave, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that has shown its effectiveness for both physical and mental health conditions. ACT uses acceptance, mindfulness, commitment, and behavior change strategies to increase psychological flexibility. Psychological flexibility can be defined as contacting the present moment, and based on the situation, changing or persisting in behavior in the service of chosen values. This is established through six core processes including acceptance, defusion, present moment awareness, self-as-context, committed action, and values. The aim within ACT is to reduce the dominance of pain in a person’s life through the development of psychological flexibility.

Unlike pain neuroscience education, and other psychological approaches, ACT does not focus on pain reduction, changing thoughts or modifying pain beliefs – even though this may occur. The ultimate goal in ACT for pain is to defuse from the influence of language and cognition over behaviour and support the clarification of values, so those living with pain can take action and return to a rich, full, and active life. An ACT informed approach to pain care does not seek to stop, eliminate, or control pain, but instead, an ACT practitioner fosters an open approach toward human pain and suffering, and redirects behavioural repertoires inline with personally held values and goals. One of ACT’s greatest strengths lies in its ability to address pain-related anxiety and depression, as well as improve functional outcomes among a variety of chronic pain populations (11, 12).

The incorporation of cognitive and behavioural techniques such as ACT into the praxis of physical therapy allows professionals to apply Psychologically Informed Physical Therapy (PIPT), a biopsychosocial approach to pain rehabilitation. PIPT integrates principles of pain psychology into conventional physical therapy evaluation and treatments, and imparts cognitive-behavioral skills to help patients effectively self-manage pain. (13). However, the adoption of PIPT is dampened not only by the mentioned gaps in pain education in current entry-level physical therapy curricula, but also by reports of inadequate professional training provided post-graduation, a recurrent issue arising in past efforts to train physical therapists in the use of biopsychosocial interventions (14, 15, 16).

The Integrative Pain Science Institute (IPSI) recently conducted a physical therapist-led ACT for Chronic Pain course aimed at training physical therapists and other licensed healthcare professionals who treat pain. This pilot study summarizes and discusses results of a post-course survey that sought to answer the following research question: What are physical therapists’ perceptions of learning and implementing ACT for chronic pain to treat musculoskeletal pain conditions?

Study: Materials and Methods

Study design. An ACT for chronic pain course was taught by a physical therapist (JT) with over 25 years of training post-graduate physical therapists in integrative pain care. The course was delivered online over 8 weeks. New content was delivered weekly via email and total training time was 30 hours. The course was directed to physical therapists and other pain practitioners, and a total of 65 enrollees completed the course. Over 90% of course participants registered identified as physical therapists. The remaining participants included psychologists, occupational therapists, nurses, and health coaches Participants could review the training materials as many times as desired. Training also included 4 live group web-conference coaching calls (120 min each) which consisted of questions and answers, role playing, experiential exercises, and discussion of situation-specific intervention approaches. One call was conducted 4 weeks into the course, another at the end of the course (8 weeks), and the remaining two calls were held after the course’s end date at week 12 and week 16, respectively. In addition, an online forum was set up for open networking and open communication between trainer and trainees in between the coaching calls.

The training focused on teaching theoretical and practical aspects related to the core principles of ACT: 1) Relational frame theory, functional contextualism, and the science supporting ACT; 2) workability and experiential avoidance; 3) present moment awareness and self-as-context; 4) defusion; 5) acceptance; 6) values; 7) committed action; and 8) a practitioner manual and protocol for use use in the clinic. Each topic included examples of metaphors and activities to effectively deliver ACT for chronic pain in the context of physical therapy practice. A tool to self-rate the basic ACT therapeutic stance and core competency was also provided as a measure of self-assessment. A full review of the training outline can be found here.

Course evaluation. At the end of the course, participants were asked to complete a voluntary 15-question online survey indicating their satisfaction with the training as well as their perceptions of learning and implementing ACT to treat musculoskeletal pain conditions. The survey was anonymous; no identifiable data on any individual was collected. The course survey questions were modeled after the overview of themes and sub-themes described by Holopainen et al., with regard to learning and implementing a biopsychosocial intervention in the management of musculoskeletal conditions (14)

RESULTS

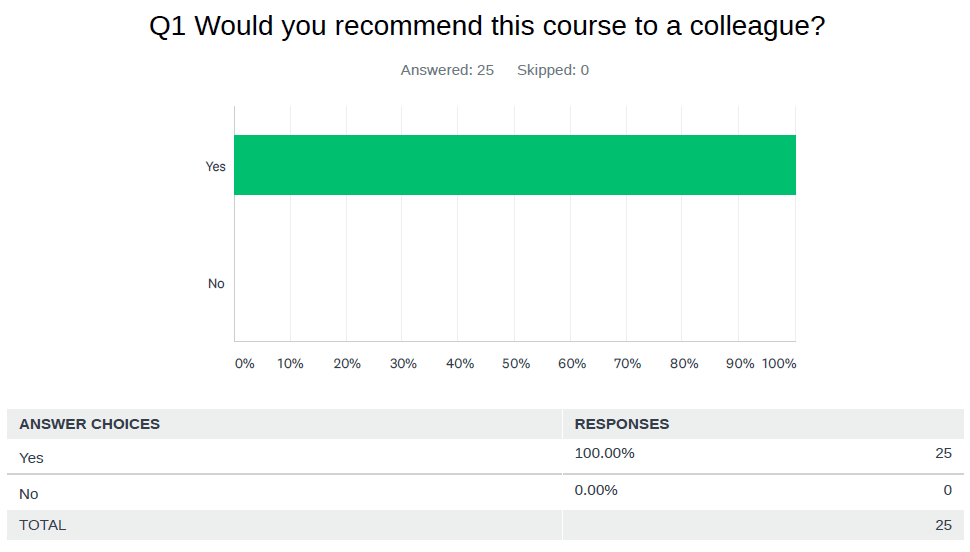

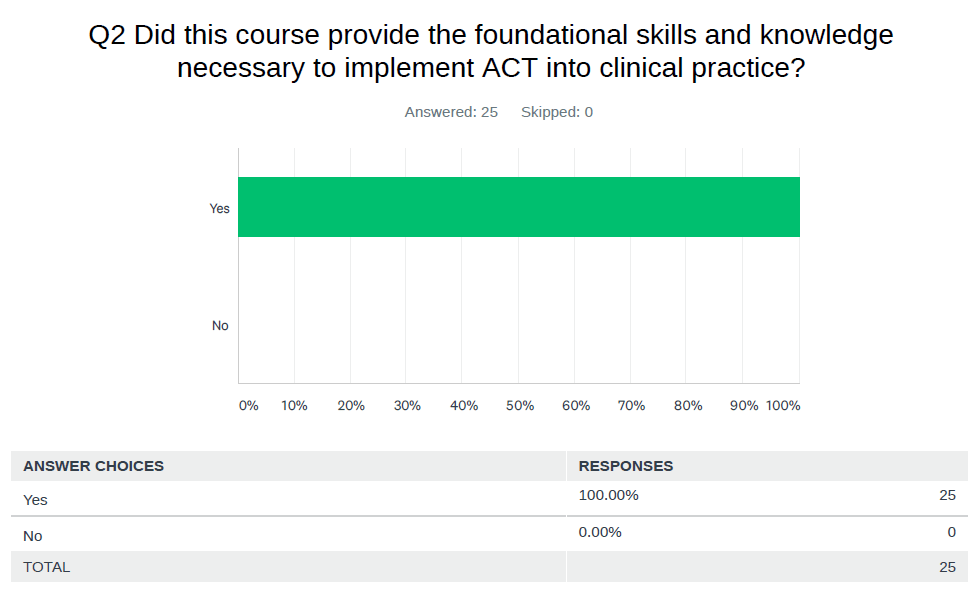

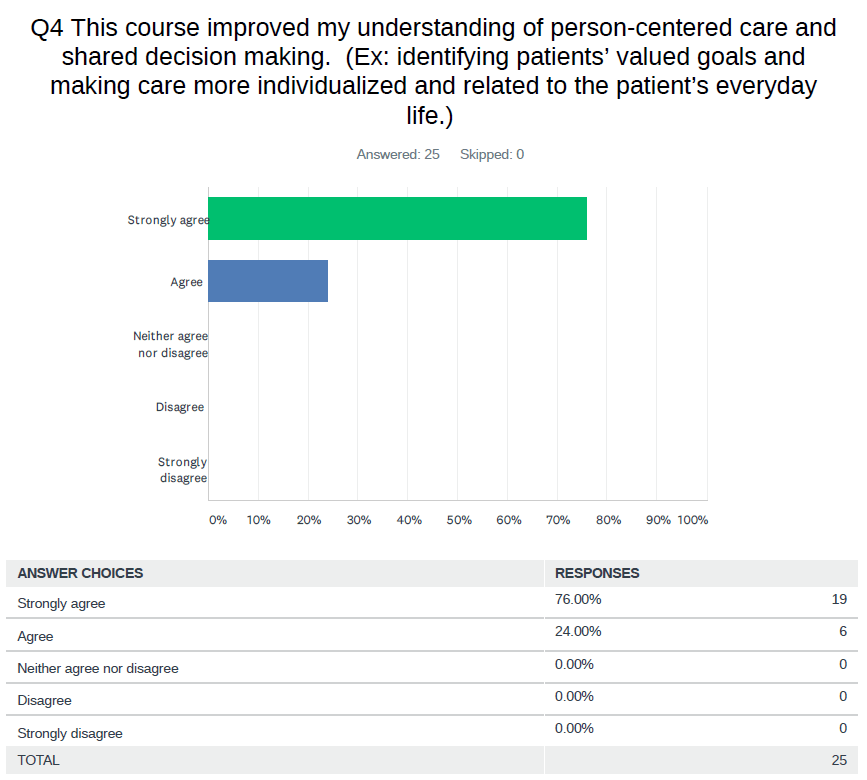

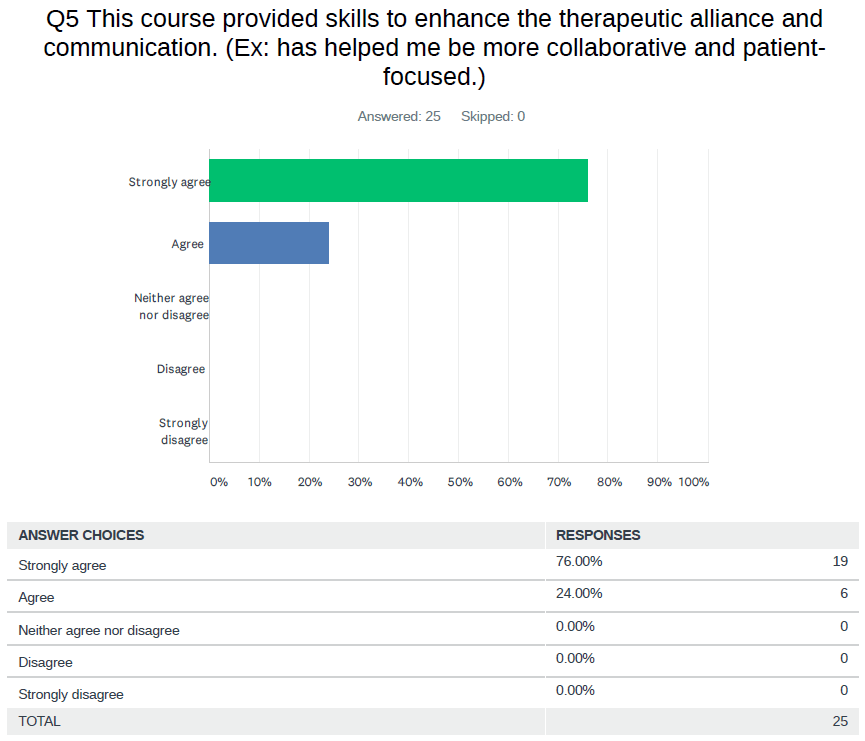

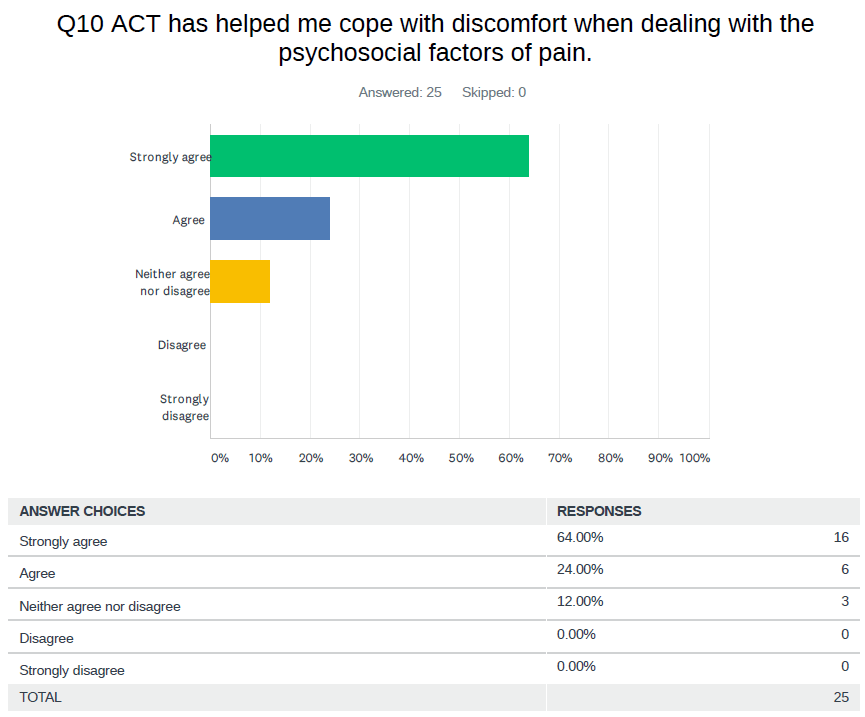

Participants’ evaluation of the ACT course for chronic pain was conducted via an anonymous survey administered four months after the course’s end (see Table 1). The survey, completed by 25 participants, sought to obtain participants’ valuation of the training received, as well as a preliminary measure of its effectiveness upon translation into real-world practice environments. Participants’ perceptions about the course were highly positive. Relevant points identified from survey responses included:

Question #2: 100% of participants reported learning foundational ACT skills necessary to implement it into physical therapy practice.

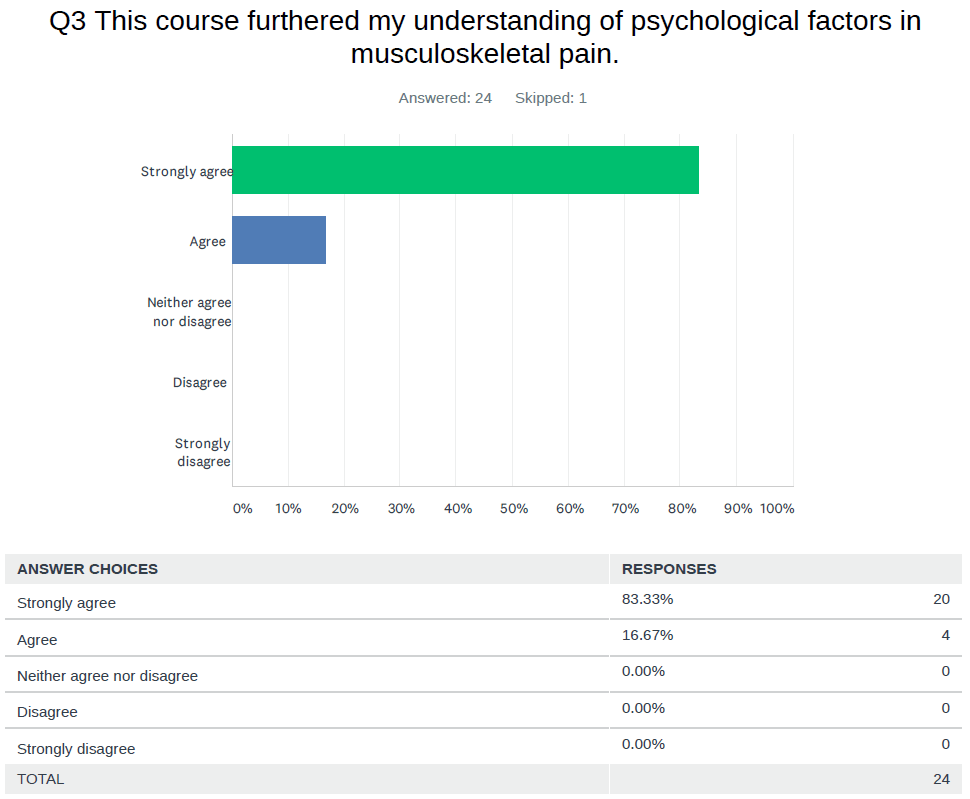

Question #3: 100% of participants reported indicated that the training furthered their understanding of psychological factors involved in musculoskeletal pain.

Question #7: 86% of participants reported agreed that the training increased their confidence level in managing musculoskeletal pain.

Question #9: 91% of participants reported agreed that the training led to improved job satisfaction.

Question #11: 95% of participants reported reported that the training was useful for clinical practice.

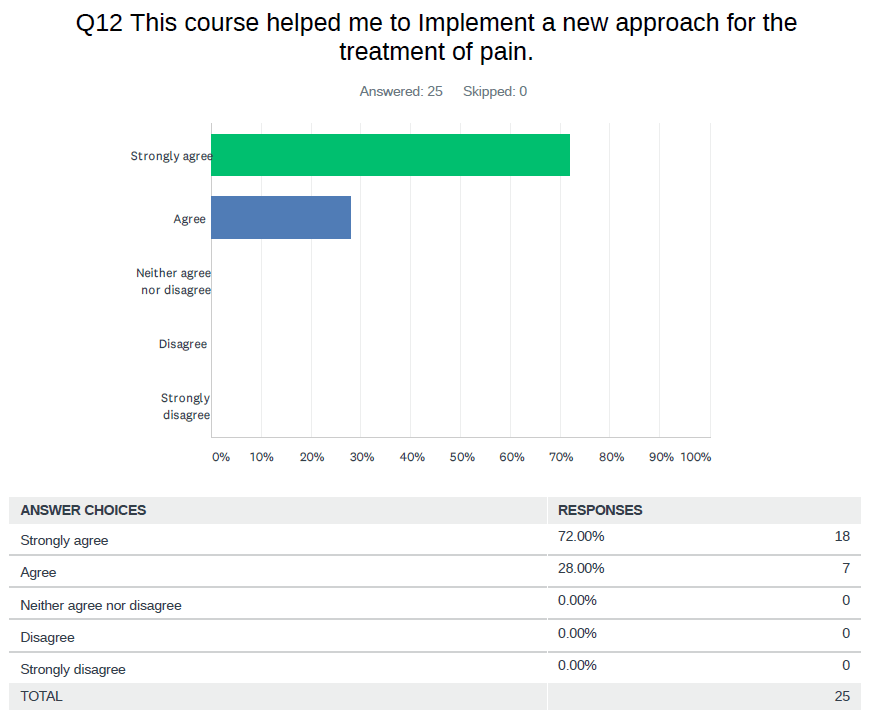

Question #12: 100% of participants reported indicated that the training helped them implement a new approach to treating musculoskeletal pain.

In addition, 7 relevant sub-themes regarding the ACT training emerged from the open-ended question #15 (What was your overall impression of the course?) See Table 2 for a full list of open-ended question responses.

- The training filled a knowledge gap in understanding of how to assess and treat psychological factors related to pain.

- A mixture of prerecorded video training, reading, and experiential exercises were critical to reinforce learning.

- Coaching calls were a useful part of the training and helped to translate course knowledge and implement into clinical practice.

- Having an opportunity to practice in a group setting with like minded peers was a critical component of confidence building.

- Ongoing communication, networking, and mentorship via the online forum allowed participants to complete the course material on-time, stay connected, and share stories and experiences about implementing the material in practice.

- The ACT stance of not changing pain or related psychological content (example: not changing thoughts, pain related beliefs, reconceptualizing pain) may run counter to other psychologically informed approaches found in physical therapy practice and took some time for practitioners to process and integrate with other pain education and psychosocial theories of pain.

- Some practitioners expressed that ACT helped them cope with work-related stress and burnout and to drop the struggle of fixing or curing every patient with pain.

Q15: What was your overall impression of the course? What went well? What could have been improved?

20/25 participant responses.

Participant #1: “Wonderful course! I thought the pace and content volume for each section was excellent— plenty of content to go back to mull on while also immediately applicable if I went through certain sections more quickly. ACT provides a hope-filled and very personal, client-specific approach to moving towards a life of patient-identified-meaning in spite of the presence of chronic pain. I especially appreciated live coaching calls—it was very useful to discuss as well as practice ACT with others who are learning ACT.”

Participant #2: “Course was great. Coaching calls were really helpful, and made me feel supported. Self assessment was also really nice. It would be cool if the self assessment could happen online and compare your answers from beginning to end.”

Participant #3: “Excellent, strong resources, great support via coaching calls, very open and accepting teacher!”

Participant #4: “Well designed & taught. good patient examples a lot of information that I need to review over & over so I’m grateful its online & accessible to me. If possible, could a real time or taped interaction be shown of therapist & client going through various ACT concepts.”

Participant #5:“I liked the format! Perfect to fit into work schedules. The calls were interesting although I only attended 1 live. I appreciate having the link even after the course. Life event and COVID had me a little distracted in the last week. I’ve done CBT for 30 yrs so this is a shift… “

Participant #6: “You do a wonderful job with the metaphors and meditations. I would like to see them in an audio format to assign and share with my clients until I am more comfortable doing on my own. It was a very well done class. Thank you!”

Participant #7: “This course was awesome, and Joe is absolutely amazing. I’ve taken enough courses where the content is good, but it feels like the instructor is very tunnel vision focused on their method (and nothing else), and the course is just a money maker to them. This was completely different. Joe is clearly an exceptionally skilled, knowledgeable and compassionate clinician and teacher who truly cares about his students. I am so incredibly grateful to him and this course. This content is going to take time to absorb and feel competent in, but I can tell it is going to be well worth the effort and discomfort of being out of my comfort zone. Thanks, Joe for being so generous with your knowledge and time!”

Participant #8:”Great course, happy to recommend”

Participant #9: “Went well. I am a health coach and have lived with CRPS and chronic pain since 1994. found info helping when coaching and running support group. similar to what i did way back when to move forward.”

Participant 10: “It was great overall. Thank you”

Participant 11: “Excellent course with great support through the online group and the coaching calls.”

Participant 12: “Need more practice at it but everything was really great!”

Participant 13:”Loved it. I can’t think of any improvements needed. Great content and usable handouts for immediate use. Thanks!”

Participant 14: “I liked the layout of the course with mixture of webinars, exercises and written information. I particularly liked that we were able to download information to use with clients. There is a lot of information to cover and I feel that I need time to practice and go through it more in my own time to feel that I can implement it successfully with patients and work towards the outcomes we intend together, it does take a bit of a paradigm shift in some respects as a physiotherapist and I think I have to give myself time and permission to work at it. I really enjoyed the content and feel excited about using it and further enhancing my ACT knowledge and experience, thank you!”

Participant 15: “I was impressed with the overall content. I thought examples of real patient interaction – in a written dialogue format – for each of the 6 elements of ACT would have been helpful”

Participant 16: “I really enjoyed this course. Not only does it enhance my PT practice with regard to chronic pain patient care, but it is helpful for EVERYONE, myself included. I liked the flow of the course from week to week, and how previous ground would be reinforced as skills and concepts were built upon. I definitely need to work more with the material to develop proficiency, but this was a sound foundation.”

Participant 17: “I really liked the course. As a support group leader and individual with chronic pain I think it is very fitting in teaching one not to ignore their pain but to focus on what’s important to them to move forward. We all have a right to live the life we want.”

Participant 18: “This course was exactly what I needed. It filled my knowledge gap on how to put my understanding of how the brain works into practice with my patients. Prior to taking the course, I had been listening to many lectures on the new findings of how the brain/behavior works, as well as watching Robert Sapolsky’s Stanford course on “The Biology of Human Behavior” (25 lectures posted on youtube). I found this base knowledge necessary for implementing the course as well as I have. I feel that some review of neurology and basic brain function (or references for self study) may be helpful to better implement the strategies presented. Thank you so much for this course. I don’t think there is anything else like it out there.”

Participant 19: “I thought the course content was very thorough and provided me with a comprehensive understanding of ACT.”

Participant 20: “Helpful and excellent course.”

The results of this small pilot course and training experience adds to the existing literature and confirms the value of specific training provided to foster psychologically-informed skills using ACT for physical therapists and other pain practitioners.(17).

Dr. Tatta’s simple and effective pain assessment tools. Quickly and easily assess pain so you can develop actionable solutions in less time.

DISCUSSION

Chronic pain continues to impose a huge toll on the economic, social, and mental wellbeing of those affected. Despite wide recognition of the necessity for alternative treatment options, adoption of psychological strategies by healthcare professionals, including physical therapists, lags well behind medical innovations and drug-based approaches that are generally costly, potentially dangerous, and oftentimes ineffective. To properly conceptualize and implement into practice the biopsychosocial principles of patient care, physical therapists need to evaluate and be prepared to address a multitude of biological, psychological, cognitive, and social factors.

The usefulness of ACT delivered by physical therapists to improve pain self-management and quality of life in people living with pain is supported by recent research (9, 10, 16). A recent RCT contrasted outcomes of Physical Therapy informed by ACT (PACT) versus usual care Physical Therapy for adults with chronic low back pain. Results showed that PACT was associated with significantly higher short-term improvement in disability, patient specific functioning, physical health, and treatment fidelity (9). Meanwhile, a single-arm study that evaluated outcomes of an 8-week program of combined exercise and ACT directed to chronic pain patients reported improvements in most outcomes post‐intervention and maintenance of many changes at one-year follow-up (10).

However, many efforts to train physical therapists in biopsychosocial interventions have so far fell short of expectations, leading to incomplete understanding and fragmented delivery of psychologically-informed care. Recent research reviewed 12 published studies to evaluate physical therapists’ perceptions of learning and implementing biopsychosocial interventions to treat musculoskeletal pain. The conclusions stressed that although physical therapists “reported a shift towards more biopsychosocial and person-centered approaches, the training interventions did not sufficiently help them feel confident in delivering all the aspects” (of the specific therapies) (14). Another study reviewing 5 controlled randomized trials (CRT) concluded that “with additional training, physiotherapists can deliver effective behavioral interventions. However, without training or resources, successful translation and implementation remains unlikely” (15). In addition, a pioneer effort to implement ACT into a physical therapy-led pain rehabilitation program underscored that physical therapists were uncomfortable with the shift from “fixing” towards “sitting with”, proposed by the ACT principles (16). Therefore, although physical therapists are in a key position to treat pain conservatively, and prevent overuse of both over-the-counter and prescription analgesics for chronic pain conditions through cognitive/behavioral methods, there is a clear need to provide them with quality training that maximizes the chances for effective translation into practice.

Importantly, the feedback provided by physical therapists who completed our training on ACT for chronic pain indicated both high satisfaction with the training provided and increased confidence in delivering ACT in their practice. Although the window of time provided to assess whether the learned contents could be effectively translated into practice was limited (answers to the questionnaire were recorded four months after the course’s end), all participants agreed that the training was optimal and the course helped them to implement a new approach for the treatment of pain. Future studies should explore treatment fidelity, long term outcomes, and the development and validation of a scale to measure knowledge and concepts, skills and techniques, and conceptualizing psychological flexibility within physical therapist practice.

In conclusion, both our own and previous experiences strongly suggest that ACT may be very valuable to adapt to the practice of physical therapy and the complex clinical and psychosocial environments represented by many chronic pain conditions. To this end, expert training and counseling in delivering ACT within PIPT precepts will help pain practitioners to provide effective treatment and improve the quality of life for people living with pain.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the professionals who responded to the course survey and for their commitment to improving the delivery of safe and effective pain care.

Funding

The author received no specific funding for this work.

Declaration of interest

Joseph Tatta receives fees for providing clinical workshops for health care professionals in the management of musculoskeletal pain.

Suggested Citation

Tatta, J. (2020) Physical Therapists’ Perceptions of Learning and Implementing Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Chronic Pain: A Pilot Study on the Integrative Pain Science Institute Experience. New York, NY: Integrative Pain Science Institute. Retrieved from: www.integrativepainscienceinstitute.com/physical-therapists-perceptions-of-learning-and-implementing-acceptance-and-commitment-therapy-act-to-treat-chronic-pain-a-pilot-study-on-the-integrative-pain-science-institute-experience/

Joe Tatta, PT, DPT is the Founder of the Integrative Pain Science Institute, a company dedicated to reinventing pain care through education, research, and professional training. He has 25 years of experience in physical therapy, integrative models of pain care, leadership, and private practice innovation. He holds a Doctorate in Physical Therapy, is a Board-Certified Nutrition Specialist, and ACT trainer.

REFERENCES

1- Tompkins, D. A., Hobelmann, J. G., & Compton, P. (2017). Providing chronic pain management in the “Fifth Vital Sign” Era: Historical and treatment perspectives on a modern-day medical dilemma. Drug and alcohol dependence, 173 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S11–S21.

2- Chou, R., & Shekelle, P. (2010). Will this patient develop persistent disabling low back pain?. Jama, 303(13), 1295-1302.

3- Theunissen, M., Peters, M. L., Bruce, J., Gramke, H. F., & Marcus, M. A. (2012). Preoperative anxiety and catastrophizing: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association with chronic postsurgical pain. The Clinical journal of pain, 28(9), 819-841.

4- Dowell, D., Haegerich, T. M., & Chou, R. (2016). CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain–United States, 2016. JAMA, 315(15), 1624–1645.

5- British Pain Society. (2013). Guidelines for Pain Management Programmes for adults. Retrieved from https://www.britishpainsociety.org/static/upload

6- Zadro, J., O’Keeffe, M., & Maher, C. (2019). Do physical therapists follow evidence-based guidelines when managing musculoskeletal conditions? Systematic review. BMJ open, 9(10), e032329.

7- Hoeger Bement, M. K., St Marie, B. J., Nordstrom, T. M., Christensen, N., Mongoven, J. M., Koebner, I. J., Fishman, S. M., & Sluka, K. A. (2014). An interprofessional consensus of core competencies for prelicensure education in pain management: curriculum application for physical therapy. Physical therapy, 94(4), 451–465.

8- Bement, M. K. H., & Sluka, K. A. (2015). The current state of physical therapy pain curricula in the United States: a faculty survey. The Journal of Pain, 16(2), 144-152.

9- Godfrey, E., Wileman, V., Holmes, M. G., McCracken, L. M., Norton, S., Moss-Morris, R., … & Critchley, D. (2019). Physical therapy informed by Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (PACT) versus usual care physical therapy for adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Pain.

10- Casey, M. B., Cotter, N., Kelly, C., Mc Elchar, L., Dunne, C., Neary, R., … & Doody, C. (2020). Exercise and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Chronic Pain: A Case Series with One‐Year Follow‐Up. Musculoskeletal Care, 18(1), 64-73.

11- Sturgeon, J. A. (2014). Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain. Psychology research and behavior management, 7, 115.

12- Veehof, M. M., Oskam, M. J., Schreurs, K. M., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2011). Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PAIN®, 152(3), 533-542.

13- Keefe, F. J., Main, C. J., & George, S. Z. (2018). Advancing psychologically informed practice for patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain: promise, pitfalls, and solutions. Physical therapy, 98(5), 398-407.

14- Holopainen, R., Simpson, P., Piirainen, A., Karppinen, J., Schütze, R., Smith, A., … & Kent, P. (2020). Physiotherapists’ perceptions of learning and implementing a biopsychosocial intervention to treat musculoskeletal pain conditions: a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Pain.

15-Hall, A., Richmond, H., Copsey, B., Hansen, Z., Williamson, E., Jones, G., … & Lamb, S. (2018). Physiotherapist-delivered cognitive-behavioural interventions are effective for low back pain, but can they be replicated in clinical practice? A systematic review. Disability and rehabilitation, 40(1), 1-9.16- Barker, K. L., Heelas, L., & Toye, F. (2016). Introducing Acceptance and Commitment Therapy to a physiotherapy-led pain rehabilitation programme: an Action Research study. British journal of pain, 10(1), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463715587117