Welcome back to the Healing Pain Podcast with Sinéad Dufour, PT, PhD

Pelvic girdle pain is typically caused by unevenly moving joints, making the bones less stable and mobile. Pregnant women often experience this painful sensation, but it must never be treated the same way as non-pregnant people. Dr. Joe Tatta reframes pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain beliefs with Dr. Sinéad Dufour, Associate Clinical Professor in the Faculty of Health Sciences at McMaster University in Canada. She discusses why this chronic pain still has a lot of misconceptions and continues to be mistreated despite the mounting evidence around its psychosocial and physiological factors. Dr. Sinéad also explains how women can stay resilient throughout pregnancy by paying more attention to biomechanics than their individual (and potentially incorrect) beliefs.

—

Watch the episode here

Listen to the podcast here

Subscribe: iTunes | Android | RSS

Reframing Pregnancy-Related Pelvic Girdle Pain With Sinéad Dufour, PT, PhD

We’re discussing how to reframe pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain beliefs. My guest is Dr. Sinéad Dufour. She’s an Associate Clinical Professor in the Faculty of Health Science at McMaster University in Canada, and conducts research in both the schools of medicine and rehabilitation science. Her current research interests include conservative approaches to manage pelvic floor dysfunction, pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain, and interprofessional collaboration models to enhance pelvic health. Sinéad engages in clinical practice through her work as the Director of Pelvic Health Services at The World Of My Baby, a perinatal care center in Ontario, Canada.

Dr. Dufour is an advocate for women’s pelvic health, and a regular invited speaker at conferences around the world. On this episode, we discuss risk factors for pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain, and why there’s a need to reframe the treatment of pregnancy-related and non-pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain.

Despite mounting evidence of the role that psychosocial and physiological factors play in pelvic girdle pain, it continues to be mostly misunderstood and mistreated, and really approached as a purely biomechanical issue, which is why this episode is important. People who experience persistent pain and other symptoms during pregnancy can be at risk for long-term physical, as well as mental health outcomes. Without further ado, let’s begin and let’s meet Dr. Sinéad Dufour, and gain a deeper understanding of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle.

—

Sinéad, welcome to this episode. It’s great to have you here.

Joe, it’s great to be here.

I’m excited to speak with you about this topic. It’s one we have not covered on the evolution of the Healing Pain Podcast. As we know, women in pelvic girdle pain is an issue, and it’s something that many women’s health specialists see, but particularly women’s health physical therapists, and pelvic health physical therapists. I’m excited to speak with you. I know a lot of what we’re going to talk about is that you do have published and wrapped around on some evidence, so everyone is going to read about what you say, take notes intently. I always tell people, “Take some notes as you’re reading.” I also want to point them to that evidence-based article. Tell us where that article can be found before we start to chat.

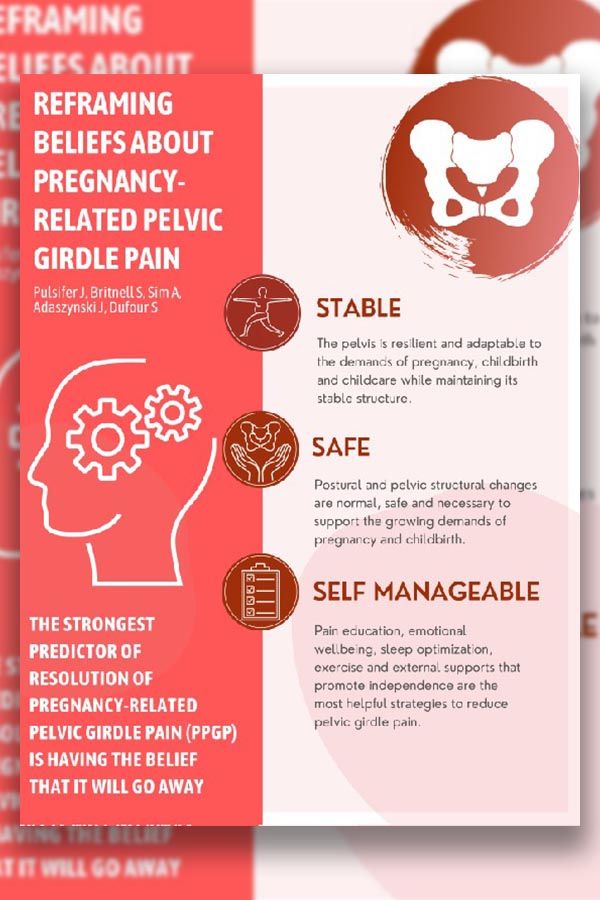

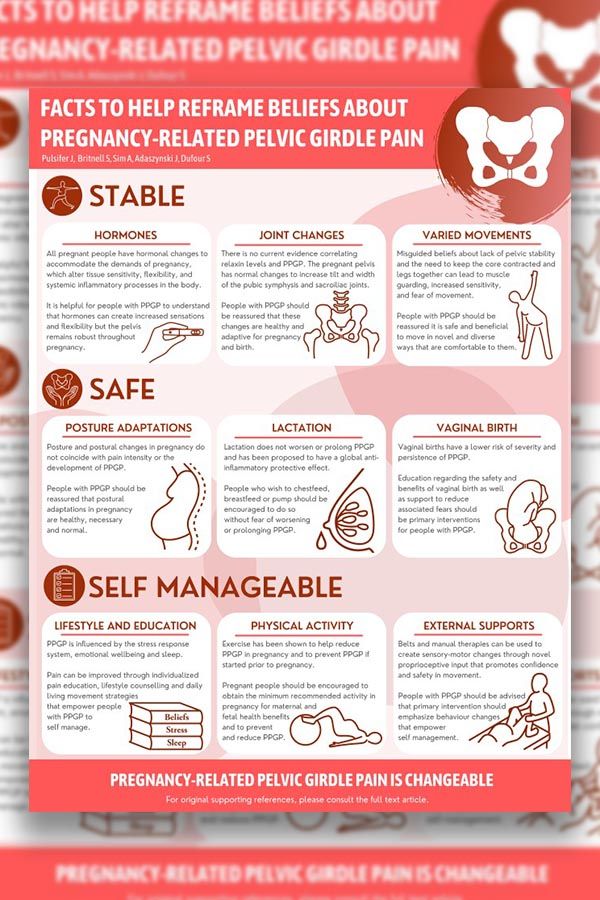

This is an article in the British Journal of Sports Medicine. It has a nice succinct summary, but also an infographic. That punctuates some of the key points and really where we have to change our thinking on this issue. Hopefully, it’s easy for practitioners to understand and digest, and then also those people who have pain.

Tell us what the title of that article is because people can obviously go into Google and put British Journal of Medicine and the title is what?

It’s called Reframing Beliefs Regarding Pregnancy-Related Pelvic Girdle Pain. It is essentially mapping out why, and the state of the science to convince us that we need to reframe our current beliefs on this issue if we are wanting to help people.

Reframing, which means how our thoughts and what we believe about a certain topic impacts our behavior, our choices, and our health. Why is it time for us to reframe pelvic girdle pain at this time?

This is a great place for us to start, Joe. Your whole show is all about trying to translate this evolution in science when it comes to understanding pain. I feel like from the perspective of a physiotherapist, and I mean I teach at McMaster University, so I’m a clinician and I’m also a professor. I’ve had a chance even to witness, even with physiotherapy students, how they’re understanding how to conceptualize a pain experience in an individual differently and approach it more from a multifaceted perspective, in accordance with the our evolved science.

It’s so interesting that with this presentation, this issue of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain, there’s a real resistance to wanting to apply everything we know about pain to this particular pain experience. It’s really interesting. I feel like all of us are moving a little bit slower than some of us might like, but in the direction of this evolution that this is a pain experience that should also be moving along and seems to be cemented.

It’s time that perhaps even as researchers and clinicians, maybe we’re coming up with better ways to mobilize the information, which is the whole point around the infographic so people understand that the state of the science is applied to this scenario too, because we have to move away from thinking about this issue to do with stability and relaxing, “It’s just a part of the pregnancy and it’s inevitable. It’s going to get worse as the pregnancy moves on because that’s what the driving factors are.” These things are not true. They’re not substantiated. They actually can cause a lot of fear and make the whole situation worse. It is time for us to use all our insight and use it to reframe this scenario just like we have other pain conditions.

You mentioned resistance. When you say resistance to the concept, where have you noticed that you’re being met with pushback or stress around this topic? Is it coming from one particular person, a particular group? Where do you notice this the most?

To be honest, I actually notice it across many different areas, which points to me that the story that has been told, that when we’re pregnant, we have this hormone relaxin, and relaxin makes the structures relax and more malleable. It’s such a plausible theory that this relaxing hormone is going to make things unstable, and surely that is then why people are having pain. It’s a story that has been so sticky.

It’s interesting. I see it in my students who actually are presented. We do all problem-based learning at McMaster University, so we do problems related to this issue at the very end of the students two year curriculum, so they’ve learned all about nociplastic pain and persistent pain and the biopsychosocial approach. They’ve learned all of that and have been immersed and scaffolded in that in different ways. At the end, we come to this issue. Without fail, every single year, students like forget all that and want to go back to my biomechanics.

Similarly with clients that I interface with and where I practice at The WOMB, The World Of My Baby, I really focus in perinatal care. This is a huge population I see as people who have this pain experience when they’re pregnant or in the first year postpartum. A huge proportion of them, either themselves, have these notions of why they’re having this pain just from their understanding from culture, or have been told to this by very well-meaning practitioners. I do think it is across the board that there is this false understanding of what’s at the root of this particular pain experience.

Let’s take a little example. Before you and I hopped on, I did some googling and searching because it’s always fascinating as to go online and start to look up different topics about pain, to get all sorts of things from the brain to certain herbs and nutrients. Let me read something that I found on pelvic girdle pain, and then you can break this down for us, and explain pelvic girdle pain, how you would like us to understand it.

This is what it said online, “Pelvic girdle pain is typically caused by the joints moving unevenly, which can lead to the pelvic girdle becoming less stable and mobile and very painful. As your baby grows in the womb, the extra weight of your child, and the way you change your sitting habits and posture will put more strain on your pelvis.” Now, you and I read that, and we have a background in physical therapy, in health, and in pain science. I was trying to read it through the eyes of a woman who’s pregnant, who’s suffering by the pre or postpartum with probably chronic pain. They read that, and what’s the first thing that they think?

I think the first thing people think honestly is that sounds plausible. In ways, it sounds like that could make sense. It’s a plausible theory. Then the next thing I think people will think is, “If this is related to my pregnancy, and I’m going to get more pregnant, this is a scenario that’s going to get worse. How on earth am I to birth my baby through this structure that is already really uncomfortable?” To the point that this issue is quite debilitating for people functionally, and them trying to fast forward to what state they’re going to be in, and how on earth are they going to birth a baby with a pelvis in that state? Then how on earth are they going to take care of a child after that?

That to me is exactly what I would expect, and it’s actually what I see in practice. I see that play out every day. The real issue with that is that it’s wrong. What you actually described is almost exactly what has been described in the literature previously because it very much is what we thought was going on. It’s just that those theories have actually been disproven. We have a systematic review that confirms that relaxin does not at all correlate with pain state. Does it correlate with increased movement? Yes, but we have no correlations that increase movement correlate with more pain. We also see that this is a scenario that pops up much more frequently in a second or third pregnancy rather than a first.

There are no correlations showing that increase movement correlates with more pain. Share on XIf it had something to do with relaxin, wouldn’t everyone have it? Because everyone has relaxin. Wouldn’t mamas who are carrying multiples, like twins alone have threefold times of relaxin, wouldn’t we see it more with that? We don’t. Wouldn’t we see a mama having the same issue in her first pregnancy set? We don’t see that.

When you start to poke holes in the theory from that perspective, it doesn’t hold up. Quite honestly, it has been tested and looked at and synthesized that this doesn’t relate to instability or relaxin. Actually, what’s transpired over the course of the last decade as we’ve learned a lot more about pain science, what are the real actual things going on? Those have been much more well-substantiated now. They just have not been translated particularly well.

They’re going to read this and they’re going to say, “Are you saying that hormones don’t play a role in pregnancy or in the experience of pain when a woman is pregnant?”

No, we’re not saying that at all, but we’re saying it’s not how we thought. We thought the way hormones were playing a role was that hormones was essentially making a scenario where there was too much movement and instability, and then that was an issue. We know that is not the case. Do we know, for example, that estrogen, as a hormone, is a bit of a sensitizer when it comes to the pain system? We know that estrogen increases a thousand-fold in pregnancy.

Is it quite possible for people who are maybe already at a bit of an edge in their physiology, that their system with that additional estrogen, that’s a sensitizer for them? Yes, perhaps. Cortisol, which is another hormone, we have lots of data to understand what cortisol does in terms of ramping up the system. No. Hormones are always going to be relevant when it comes to a pain experience, but it’s just not how we thought. It really isn’t around the stability piece.

If a woman comes to you, and she’s on her second pregnancy. The first one went really smooth. She loved it. She was happy. She had no physical symptoms, no complaints. The second pregnancy, there’s pelvic girdle pain. She comes to you and she’s like, “Why is this happening? My first one was a breeze, and nothing has changed. My health is the same. I eat the same. I move the same. Why is this different?”

You answered some of that there, Joe, but always my first question back is, “What do you think? What do you think is actually going on? What do you think might be causing the pain?” In that scenario you said, it indicated, “Everything is the same. I’m stumped.” I still probably would ask that. What I often get back is, “I’m sitting a lot more. My posture hasn’t been that as good because I’ve been pairing around my previous child. I think my core isn’t as strong as it used to be.” These are the answers I tend to get back. How I will usually meet that is say, “Okay, that’s plausible,” because at the end of the day, anything with the human body plausible and possible. We still only know a fraction of the complexity.

I will say, “What I’m going to go through with you now is the actual known risk factors or the things that are much more likely to be at the root of it. Then we can see if we think any of those apply to you.” I literally will go through the established risk factors. One of them being, the top one, previous trauma. That is our top risk factor. I’ll say, “Top risk factor is actually a previous trauma. If you reflect on anything that happened in your last pregnancy or the birth or the postpartum period, was there anything that lands for you there?” Many times, it’s, “Yes, that first birth, I went in expecting this or this happened,” or maybe it’s not the birth, but in the postpartum period. Baby had a tongue and lip tie, and that was really stressful. Going to appointments and the breastfeeding is difficult. It starts to give us some clues in terms of what might be happening and creating a bit of a signature here in the system.

That’s the first one is trauma. Where that will pick up too is maybe a mama is having no issues the first time, but then between that pregnancy and the next one, there’s been a miscarriage in between. Or things haven’t gone as well, and now there have been lots of fertility treatments that have happened. It’s understanding that risk factor. Then it’s going to the next one, which is around dissatisfaction with work. This is the next established risk factor that a lot of people don’t know. For example, I had a lot of teachers through COVID, and of course I was doing a lot of virtual care, come to have an appointment with me because of this pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain.

It’s like your scenario saying, “I was fine this time, but this time I do. I think it’s because I’m sitting more at work. I think that’s the problem.” Me saying back to them, “The environment and the morale around teaching right now with COVID, would you say that’s the same as it was with your job before?” Always, I would be met back with, “No. Work is a real strain and drain.” Helping them to understand will the data that support that being much more likely to be driving some of this issue actually than the postural things?

I go through the list. The next one is high BMI. The proposed mechanism there is inflammation. The next one is smoking. The proposed mechanism there is inflammation. The last one is lack of belief of improvement. This hits the head on that scenario you said to me before in terms of, “This is related to your pregnancy, and you’re only going to get more pregnant. You’re going to have no belief that this is going to get better. In fact, you’re going to believe it’s going to get worse.” That is a huge risk factor for that issue.

We can see where that ties into unhelpful notions about what this thing is all about. That also predicts persistency. This is usually how I go with my clients. I’ll try to get from them, “What are they thinking first?” I’ll say, “This is actually what we know. There’s a lot we don’t know, and every person is different, but these are the things we do know.” Then it can at least be a helpful starting point for people because they can match to what things might be relevant to them. I can start to get them thinking along the lines more of the physiology that might be driving their circumstances versus the mechanics.

You’re saying beliefs should be as important or potentially more important than biomechanics. I know that can be a tricky place to have a conversation with our fellow practitioners sometimes, right?

Absolutely. I have been known to actually say that exact comment, “Beliefs are more important than biomechanics.” I’ve gotten some flack and some pushback with that particular phrase. I think it’s because people are really not contextualizing what I mean. This is what I try, and probably sometimes I do it better than others, but I try to make sure the person in front of me gets this. We are not saying that it’s just a matter of thinking you’re going to be fine, and you’re going to be fine. That’s not what we’re saying. It’s more helping people to understand that your cognitions, your understanding of something, lack of belief of improvement, but what does that actually do in your biology? What does that actually do in your physiology?

It does a lot of very specific things in terms of turning on your threat response, changing cortisol, driving up inflammation. There’s very specific pathophysiologic things that happens from the cognitions. I’m not suggesting that the beliefs aren’t actually rooted in legitimate biology. Actually, they are. If anything, I’m trying to help people to think more about this physiologically, and then of course we can move into all the things that will help to modulate their physiology in a calmer, happier way, so that they’re not as sensitive from a pain perspective. Cognitions are so important. We know that for all pelvic pain, and this issue is within that umbrella that cognitions are really important. How we understand and make sense of this pain experience, and how we understand our biology is really important.

What you’re trying to break down, the biopsychosocial model of pelvic girdle pain for people, which just the biopsychosocial model right there is tough. For people to understand, that can be tough. Your biology, the chemistry in your body impacts your health. Psychology, which you said wonderfully how you think impacts your biochemistry.

We’re dancing around this, and we haven’t gotten into it yet, but I want to bring it into the conversation. A lot of what we’re talking about is the social aspect, meaning how our culture, the people, and all the things around you impact your health. It’s funny because I was walking to get a cup of coffee this morning. I have to pass a New York City school, and there were tons of kids and families. I had this moment where I was like, “Life really does revolve around kids and families in a lot of ways,” like our society is. We’re a family built society.

How damaging is it that this belief system cuts through healthcare? It cuts through family and different generations. These beliefs are carried forward from one generation to the next, passed down from person to person. The one thing that you’re right about is beliefs may not always be more important than biomechanics, but beliefs are more important than biomechanics when it comes to the persistence of pain.

I would say the data for this particular pain presentation actually would show that beliefs are probably more relevant for this one, contrary to popular belief. I like what you brought up there though about the social context because that is really important. Not only do we have these beliefs around what’s driving this particular pain experience, which because it’s misguided, it actually keeps people stuck and actually sets them up for further dysfunction.

We have these whole cultural beliefs actually around birth, which I think is a big part of the issue with this particular pain experience. Our bodies are not up to the challenge of birthing. We need all these medicalized things for birth. Birth is going to be painful and scary. We see that fear in general, not just fear of movement, but fear is an important vector for this particular pain presentation.

I think culturally, the whole birth piece is part of this, and so it shows that social cultural component does really feed in strong and is something that we have to think about. I think a whole other side but related issue is the whole fear around birth and overmedicalization of birth, and that our bodies aren’t up to doing this unless we have a force without sight. It’s all of that. It’s essentially like biopsychosocial considerations for this.

You have a magic wand that you like to wave in a couple places to change all this. Obviously, people are going to read this and they’re going to share with all their friends and family to share this new belief around pregnancy and the health you can experience. How would you like to see this potentially first change?

What I would like first is for people to understand that there is a difference between a pregnancy related ache and pain, and pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain. Probably most women who have been pregnant, myself included, can at least say, “There were a couple days that I had a bit of pain somewhere, but I put a heat pack on it, or I did a little bit of extra yoga. I took it easy. I maybe took the next day off and I was fine.” They were able to manage it with their own toolbox, and being able to interpret that their body needed a little bit more relaxation potentially, and they could sort it out. That’s not what we’re talking about.

What we’re talking about with the data on this issue where we have high comorbid fear, depression, debilitating, coming off work, this is what we’re talking about, and it’s common. We have to understand that not unlike other pain experience, we’ve stepped out of nociception and stepped over into this nociplastic situation.

It isn’t going to be helpful in those situations to ever just think about the mechanics. Instead just feeling more empowered to think about what are all the different things you might be able to do to better support resilience in that system, and layering out previous traumas or at least acknowledging those as one of them. All the basic principles around developing resilience and decreasing neuroinflammation in terms of getting adequate rest and restoration and nutrition, and all of the things. It’s so much more empowering actually for people when they understand this for what it actually is.

That is what I would love for people to understand. Look at the infographic and understand this issue for what it actually is, and see that you can be very empowered to start doing things, to start supporting your system, to turn down that sensitivity knob to help the pain go away. It actually can be completely gone before you birth that baby. It is not tracking with the pregnancy. It doesn’t have anything to do with that.

Give us an idea of what’s in the infographic. Can you read us some of the data that’s there?

It’s divided into these three sections: Strong, Stable, and Self-manageable. They might be in a slightly different order, I’m doing it for memory here. It’s to cultivate. There’s so much data. Even if we look at the literature around sacroiliac joint pain that isn’t specific to pregnancy related pelvic pain, but sacroiliac joint pain. There was another great paper actually, something similar title, Changing The Narrative Of Sacroiliac Joint Pain.

The takeaway message from that review was one of the most important things is to manage fears and incorrect cognitions around pain, because that seems to be very relevant, fear and sacroiliac joint pain. The next one was helping people to understand how robust of a structure of the pelvis is. This is where that notion of strong and robust pain is. Then we have the word stable because many people look at this as an instability issue, and it’s not.

We have the piece around self-manageable for people to know that it’s not to say you can do it alone, but with some guidance, you can now understand your pain experience. You understand what’s happening and you understand different tools that you can use. It isn’t something that you need to be in a practitioner’s office every single week having them fix you. You can understand what’s happening and actually navigate your way with some tools.

Within those, we break it down a little bit further and talk about some of the things we talked about, like around the hormones. Hormones are relevant, but not how we thought. How this isn’t an issue about weak core muscles or posture. We mentioned that in the infographic. We talk about lifestyle interventions, and anything that will help to create slightly better homeostasis and less systemic inflammation.

We have a few other topics we make a mention around breastfeeding. There are some thoughts that in that postpartum period, if you’re breastfeeding longer, that’s going to maintain a hormonally altered environment for longer, and that will then correlate with higher pain. Actually, the data shows us the opposite. With breastfeeding, we have more oxytocin, which is actually anti-inflammatory. We see that it’s actually protective. If anything, some of those studies reinforce the inflammatory theory rather than the stability theory.

One of the things we do acknowledge is what we call external supports. We lump manual therapy and external garment wear into that category to say those can be helpful, as long as they are applied within the context of helping to empower someone, helping someone to feel safe and supported, not really giving the notion that someone is unstable or needs to be put back into place. There can be some great value. Then we have a thing about exercise and movement. It’s critical we get these people feeling safe in their body and able to move well. We need mamas to be fit, healthy, well, and exercising. They cannot do that if they have this pain experience that they don’t understand and they’re going downwards. They need to understand what’s happening and then start to get on a good road to health and function.

Mothers need to be fit and healthy during their pregnancy. But they cannot do that if they suffer from pain they don't understand, such as pelvic girdle pain. Share on XWe want people to know that relaxin is not the cause of your pain, and it doesn’t make your ligaments loose where your pelvic bones are going to move all over the place without your control. We want people to know that your pelvis is a strong and stable anatomical piece of your body no matter who you are. We want people to know that there are simple lifestyle tools that you can use to create resiliency in yourself as you head into or through your pregnancy, for both your mind and your body.

It’s a perfect summary, Joe.

It’s important that people hear that. As you’ve articulated, you’ve now given us a list of at least 20 or 30 things that they hear. We’re competing with decades of false news. Fake news about pelvic girdle pain basically. It’s important because this happens day in and day out of many women’s health services, not just PT clinics but OB-GYN, etc.

The other thing I would say too which is a little bit of a plug for virtual care. What’s been so interesting with COVID, I guess one of the silver linings for that has been practitioners like you and I and others really adopting through these virtual care models, but that’s also made people like us more accessible to people all around the world. I have to say, it’s been interesting for me to even see myself how this plays out in virtual care because I’m seeing people from all around the world who have been saying the same narrative about, “This thing is out of place, and it’s this, that.” They’re still struggling.

One of the silver linings of COVID-19 is teaching healthcare practitioners to adopt virtual care modes. This made them more accessible to people around the world. Share on XI’m able to do a consult with them in virtual care, applying principles of psychologically informed care, and behavior change, and some of those tenants of pain neuroscience like reframing, but also some of the mindfulness and acceptance approaches that we can do nicely virtually. Just not even being tempted to do some of the things I might be tempted to do if I was with someone in person. Seeing firsthand how effective it is. It reinforces that this does more to do with these other things, and if people can understand it and you can help guide them with the tools, they can create health in themselves really well.

You’ve mentioned trauma and resilience a bunch of times. For the one population of veterans, there are some programs they take now before they go into a place of war where they’re provided with tools to help build their resiliency. Because the higher your resiliency is, it decreases the potential or the risk factors related to trauma. Should we look at pregnancy as a traumatic experience, or at least start to prepare people with some of the same tools and have programs and services built around that?

I think there’s a good argument for that, Joe. We know predictably that there’s a high number, something like 30% after your first birth, where you’re actually diagnosed with PTSD from what just happened. If we put aside even those people who go through that process and it’s normalized for them, so they’re not even aware that they were traumatized by that. Then if we look at the people where they’re very aware that a physical trauma has happened, a third degree tear, a fourth degree tear, and forceps use, some of these things are very predictable. You’re quite right that we have good data around even different aspects of mindfulness interventions.

Tracy Donegan, she’s a midwife. She’s the Founder of a whole kind of program called GentleBirth, but it’s built into an app. Tracy and I actually have a paper submitted. What we found was individuals who were doing essentially what we referred to it as brain training, a combination of hypno-birthing, mindfulness training, but seeing that had such a positive impact, not only on their satisfaction with birth, but actually in terms of way less interventions and like the whole list that goes down.

I agree with you. I think we have to change some of the narrative and thinking and just culture around birth, coming back to that component. Having some program set up, similar to what you mentioned about the veterans to build up that resilience, could probably go a long way. Hopefully, more research continues from this initial work that Tracy and I have done.

Sinéad, it’s been great speaking with you about how we can reframe pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain, and the importance of this topic for both practitioners as well as people who are in the middle of their pregnancy or potentially even planning a pregnancy. If people would like to learn more about you and follow your work, how can they do that?

You can follow me at www.TheWomb.ca. That’s my second home, that’s my clinical practice. You can find me there. You can also find me on Instagram, @Dr.Sinead. Through my Instagram, you can link onto the my bio and it takes you to McMaster page and all my publications, and some of the other different teaching companies I work for. Those are probably the two best spots, The WOMB and then my Instagram page.

Reach out to Sinéad, and let her know how much you’ve enjoyed this episode, and the importance of this topic for women and health professionals understanding how to treat and manage pelvic girdle pain. I’m Dr. Joe Tatta. We’ll see you next time.

Important Links

- Dr. Sinéad Dufour

- The World Of My Baby

- Reframing Beliefs Regarding Pregnancy-Related Pelvic Girdle Pain

- GentleBirth

- @Dr.Sinead on Instagram

- https://www.Facebook.com/theworldofmybaby

- https://Twitter.com/dufoursinead

About Sinéad Dufour

Dr. Sinéad Dufour is an Associate Clinical Professor in the Faculty of Health Science at McMaster University. She teaches and conducts research in both the Schools of Medicine and Rehabilitation Science. She completed her MScPT at McMaster University (2003), her PhD in Health and Rehabilitation Science at Western (2011), and returned to McMaster to complete a post-doctoral fellowship (2013). Her current research interests include: conservative approaches to manage pelvic floor dysfunction, pregnancy-related pelvic-girdle pain, and interprofessional collaborative practice models of service provision to enhance pelvic health.

Dr. Sinéad Dufour is an Associate Clinical Professor in the Faculty of Health Science at McMaster University. She teaches and conducts research in both the Schools of Medicine and Rehabilitation Science. She completed her MScPT at McMaster University (2003), her PhD in Health and Rehabilitation Science at Western (2011), and returned to McMaster to complete a post-doctoral fellowship (2013). Her current research interests include: conservative approaches to manage pelvic floor dysfunction, pregnancy-related pelvic-girdle pain, and interprofessional collaborative practice models of service provision to enhance pelvic health.

Sinéad stays current clinically through her work as the Director of Pelvic Health Services at The World of my Baby (the WOMB) a family of perinatal care centers in Ontario, Canada. Sinéad has been an active member of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC) sitting on two committees and leading several clinical practice guidelines. Her passion for optimizing perinatal care and associated upstream health promotion for women stemmed from her own experience as a mother of twins. She is an advocate for women’s pelvic health and a regular invited speaker at conferences around the world.