Welcome back to the Healing Pain Podcast with Julia Chevan, PhD And Amy Heath PT, DPT, PhD

In this episode, you will meet two physical therapists who are breaking ground and have created Core Principles for the Education of Physical Therapists in the Context of the Opioid Crisis in the United States. Their work present model educators can use on a state, national and global level with regards to the development of opioid education for physical therapists and other licensed health professionals. The research which we’ll discuss all on this episode recognizes not only the role of physical therapists in the care of chronic pain but most importantly, a profession that engages patients who are at risk for opioid misuse and patients who have opioid use disorder as a primary diagnosis. This episode’s expert guests are professors Julia Chevan and Amy Heath. Professor Chevan is a Professor of Physical Therapy and the Chair of the Department of Physical Therapy at Springfield College in Massachusetts.

Professor Amy Heath is an assistant professor in the Department of Physical Therapy at Western Michigan University. Both are authors of several peer-reviewed articles, book chapters, and abstracts related to the profession of physical therapy. You’ll learn how to create Core Education Principles that physical therapists can use to educate the public, how to screen for and prevent opioid use disorder? The importance of the movement system and how physical therapists can engage in interprofessional care of chronic pain and opioid use disorder? As you all know, the care of chronic pain and the treatment of opioid use disorder is an important topic and developing education initiatives for physical therapists in response to the crisis is deeply needed. Without further ado, let’s meet professors Amy Heath and Julia Chevan.

—

Watch the episode here:

Subscribe: iTunes | Android | RSS

Developing Core Education Principles For Physical Therapists In Response To The Opioid Crisis With Professors Julia Chevan And Amy Heath

Welcome to the show Julia and Amy. It’s great to have both of you here.

Thanks, Joe.

I’m excited to be talking to both of you. It’s always fun when we do an interview and an episode where we can get more than one person on the line. Both of you chipped in and created an incredible paper that the physical therapy community and potentially other health professionals are looking at as well. It was a paper that you published in November 2019 Journal of Disability and Rehabilitation and the title of that paper is Developing core education principles for rehabilitation professionals in response to the opioid crisis: an example from physical therapy education. Both of you are physical therapists’ educators, you’re experts in PT education. I’m starting to look at what’s going on in the world of physical therapy education with regards to the Opioid crisis. Tell us how this paper came about, how the two of you brainstormed and how this idea to write this important paper?

We are both faculty members at Institutions in Massachusetts and Massachusetts in the state that’s been hit particularly hard by the opioid crisis. Part of the state response to the opioid crisis has been led by our governor, who got a working group that looked at it from the standpoint of not only what are prescribers doing but how are we educating the people who prescribe and who provides services to those who are opioid users? In our state, a bunch of professions was brought to the table to develop either principles or competencies around Opioids, medical education, dental education, nursing education, and social work education. Amy and I were sitting at a conference and we looked at each other and said, “Why not physical therapy education? Why aren’t we at the table? We have something to offer. Our patients are people who are either using opioids potentially or at risk for using opioids. We need to be at the same table as well.” That’s what got us started. Does that sound right, Amy?

Absolutely. It was a brilliant conversation.

It’s interesting because when we think about the opioid crisis, we think about prescribers and people overprescribing or not prescribing responsibly and potentially tapering off of opioids. People think, “What does physical therapy have to do with that, so to speak?” As professionals that are part of either multidisciplinary teams or even professionals that work in private practice, as solo practitioners, we’re seeing these types of patients who are struggling with these types of issues.

For us as educators, it’s not that we know that we’re seeing it. We know we’re sending students out into an environment where they’re going to see it. As physical therapists, we do a great job of educating our students around contemporary pain science. There are guidelines that we can all turn to for pain science, but what don’t do as good a job as saying there’s a public health crisis and what additional education do, we need to provide to our students? A lot of that is the impetus behind writing this paper.

You have a model that you’ve started to develop and work on and models are always useful on there. They’re living models start to grow and flourish. You have these core principles that are involved in the paper as well. Can you tell me about the model? Can you describe the model as well as some of the core principles?

Although Amy and I are the principal authors on this paper, this is a paper that was endorsed by all the DPT programs in Massachusetts, as much as where the beginning brains behind it, it was a consensus method, reaching out to all of the programs and getting feedback from everyone. As Amy and I sat down to look at this, review the literature and thought about our students out on clinical, we came to this realization that there are three patient groups who we could be seen in relation to opioids. People who have an opioid use disorder that is coming to our clinics with pain. People who are at risk of having an opioid use disorder. Maybe they don’t have one, but they’re taking opioids or they’re at risk for taking opioids. They are often people with pains.

There are people who simply have an opioid use disorder and part of the problem isn’t pain, but their real problem is the opioid use. One way of looking at the patient populations is groups of people with pain, some on opioids and some not and people who are on opioids, possibly without pain. That’s the center of the model. These three-patient populations and where they do or don’t overlap. On the outer edges of the model, which is a triangle with these two revolving balls inside it, we put the interventions that we need to make sure our students understand and the clinicians who are teaching our students, our clinical faculty understands.

One is screening and patient education is key when we’re working around opioids. The second is the concept of the movement system, which is the constructs that we own for intervention as physical therapists. The third is understanding that this is part of an interprofessional care package. That with any one of these three-patient populations, it’s not that we’re saying to the students, go for it, go it alone, but come back and talk, gather, and create into a professional team so that you can adequately address the issues for these kinds of patients.

It’s great that brought in feedback and you gathered some feedback from the other DPT programs in the State of Massachusetts. That lends a lot of support to the paper. Amy, how do these core principles tie into what some of the APTA has started to talk about, develop, and publicize both to professionals as well as the public?

Hopefully, all your readers are familiar with the ChoosePT Campaign. That’s the APTA’s campaign about choosing physical therapy as an intervention as opposed to opioids. When we think about that relative to our model, it’s about who are the patients sitting in front of our students? Some of them are in pain and taking opioids or at risk of taking opioids or have opioid use disorder as a primary diagnosis. The APTA’s initiative is about choosing PT and eliminating the opioid side of it, whereas the framework and model that we created is about those individuals that are in the heart of the opioid epidemic or potentially could be.

I like your model because it’s more inclusive. We know as professionals, there are some patients whether they’re in a certain stage of their recovery or potentially even long-term, where opioids can be beneficial. We had a lot of information that’s come through that opioids can cause harm, we know that. We’ve also seen that if you use or prescribe appropriately, they can be beneficial for people’s function as well as their chronic pain. I liked that you started to implement all that together. Helping professionals think about all three different groups that potentially we’re seeing. Pain science is something that physical therapists have cultivated as a profession and they’re excited about it. Some of it is taught in PT school. Some of it’s still taught in PT education. Other professionals are interested in it. How does pain science start to weave in with this model of care?

Pain science is reasoned in a couple of ways. For us, it’s about the idea that the populations that we’re seeing in two of those groups, we identify them as individuals with painful conditions. That means that when we’re educating our students, one part of the core of what they need to learn is the basics of pain and pain science and what we understand now to be all of the influences of pain. The model itself fits sweetly under the biopsychosocial approach to managing pain. What we are talking about when we’re talking about the core principles in terms of screening and education, which we need professional care. A lot of it is not just, we can help somebody manage their pain.

It’s also, who are the providers that you need to involve in the treatment of your patient with pain? What are the social systems that we have to work on to help somebody who has a problem related to their pain? One of the core principles talks about recognizing and advocating in a manner consistent with the knowledge that in order to have a better chance of recovery, somebody’s basic needs but be bet must be met, including safe, stable housing, primary healthcare, mental healthcare, and access to ongoing sports services. It talks to a lot of the way we understand pain, pain science, and the biopsychosocial model.

Does this apply to physical therapists working in multidisciplinary models or does this apply to the private practitioner in private practice?

I would argue that it applies to everyone because even those that are in private practice, you need to know who your resources are outside of your practice. Through these guidelines, we don’t ever want our students to go out and go at it alone. Even if you’re in private practice, we want you to go out and figure out, “I’m here in private practice, but where are my resources in the community and who do I need to reach out to if this is my patient population?”

We had these principles. They’re one of the principles. I love the paper. I love some of the diagrams you have in tables to help summarize some of the information. As you’re writing and completing this paper and you’re excited because it’s getting published in a major journal, which is awesome. What’s your vision for the profession to do with this paper and these guiding principles?

We had a good conversation about this. Our goal is to educate. By getting this paper published, it made it available to a wider audience outside of the DPT programs into the State of Massachusetts. We’ve talked a lot about PT students that we are focused on educating because that’s what Julia and I do. We’re talking about the clinicians in our community, people who potentially haven’t had this information because honestly, it’s a contemporary issue. If you’ve been out of PT education for ten years, maybe more, you may not have had any information about opioids or opioid use concerns that are happening in our communities, thinking about educating our students, educating the clinicians and those clinicians who then are taking our students as well as the primary vision for this project.

I’m going to add to that we took action on that vision. We’ve done two pieces of training and then we do the training. We invite students from across the state and we invite the clinical instructors to come to the training. We put the students in the room with the clinical instructors. At those training, we focus on basics around opioids, pharmacology, understanding the social network, the social supports, and social system. What else we do? We teach everyone how to use Narcan or Naloxone in the training. Every physical therapy student and every clinical instructor who comes and learns how do I use naloxone? Where do I get naloxone in the State of Massachusetts? Every clinic can carry it. Every clinic could have it. It’s an open prescription. You walk down to the firms and pick it up, no questions asked. We’re trying not to do these. Everyone learning opioids in their pharmacology class and everyone’s learning pain science and they’re middle-class. What does this all look like when you bring it together?

I interviewed a physiotherapist from the UK. In the UK, you can go for extra education, not very long, it’s about two months. You can earn the privilege so to speak, to prescribe and deprescribe medications, any medication as a physiotherapist in the UK. They’re excellent, well-trained physiotherapists. In some ways, their system is a little more progressive than ours, but they can go for that certification. I was like, “That’s interesting.” Having an education on Narcan is important, especially since many communities have multiple PT practices on every corner and a patient may wind up there in trouble while the other in the clinic or outside the clinic can be important. Talk to me a little about the training. You’ve done some training with therapists, what does that training look like? How many days is it? How long is it?

The two pieces of training we’ve done have been a day, a continuing education style day. We invite students from across the state, the program faculty, clinical instructors from across the different universities and colleges here. It’s open, it’s been free. We haven’t charged anybody for it. There are some plans in the work to do it again in Boston in the fall of 2020. It’s been great. Part of what’s great is that wherever we go and do it, we partner with the community organization that is working on the opioid crisis in that town or city. That’s the group that comes in and does the Narcan training. Most often, there is a lot of different community, health organizations that are doing local Narcan training. Part of what we’re trying to do is get people to understand who’s in my community? Who can I turn to? Who’s going to understand the opioid crisis in Massachusetts, on the Western side of the state versus the Eastern side of the state?

I Googled the CAPTE Accreditation standards and I skim the document a little bit. It’s a long document, a little detailed, but I skimmed it for many of the topics that we were talking about. I didn’t find a whole lot of information specifically related to opioid use disorder and opioids. CAPTE gives general guidelines that schools follow for accreditation, they don’t necessarily give specifics. You too have done beautiful work around giving specifics. How have the programs in Massachusetts, in your home state, started to adopt some of the principles that you talked about in your paper?

We left the adoption up to each program. All the faculty have been given access to the document, the faculty who are doing the adoption. They have to match it to the curriculum of the Home Institution and that can be a little bit tricky. If it’s a curriculum where everything is in its container, pharmacology in one container and pain science in one container, it might be how they’re addressing it. Many institutions have been addressing it. I know we’ve talked to our colleagues at MCPHS in Worcester and they’ve been addressing it by bringing together the different professions for education. Physician assistants, physical therapists, and pharmacology students all coming together and doing some interprofessional case conferences around cases that relate to the core principles. Amy, do you know what Simmons was doing?

When I was there, Simmons is a case-based program or tutorial-based program. Thinking about what are the cases that are being addressed and making sure that there are at least a several that are including topics around opioids and neuroscience so that students have something that they can hang onto in terms of a patient case for the content.

It could fit into a case-based learning program or it could fit into programs that have more didactic, a course for this or that you can fit in probably to a pharmacology program or a pain neuroscience program.

In all honesty, in most programs, it’s probably a little bit of everything. There’s a lot of overlap in the content.

How can other professions take this information and use it to benefit their profession and work with patients in their clinic that they’re seeing?

When we sat down and thought about writing this manuscript, we want it to have as maximum reach as possible. We targeted an international journal and a journal that would be available to all healthcare professionals. The way that we think about this is that we have the three elements, the screening an education, the interprofessional education or the interprofessional approach and then the movement system. It might be that somebody like an occupational therapist substitutes the movements system for occupational health. Speech-language pathology substitutes communication for the movement system. Thinking about, for each profession, what is your scope of practice? What are the things that are important to you collectively and allowing that model to inform what you’re doing?

You did a poster on this at the World Confederation for Physical Therapy, right?

Yes, we had a poster at the World Confederation and we presented some of our earlier ideas at the Educational Leadership Conferences as well. We’ve tried to disseminate this as much as we can. Interestingly, at WCPT, the people most interested in this were some physios from the UK in part because they’re beginning to have conversations about whether there are limits on the prescribing a pharmacy for some of the physios. One of those limits they’re looking at is Opioids.

How has the local DPT community in the United States started to respond to your paper?

I don’t know if you have, Amy. I haven’t heard anything beyond our state. The State of Massachusetts, everybody’s adopted.

Having transitioned from Massachusetts to Michigan, I can recall after we did our presentation at the Education Leadership Conference that there was a lot of support and a lot of interest from people in the community and one of those people was in the State of Michigan. Thinking about how we can move this forward to other States so that PT students across the nation are getting information around the epidemic. It’s been the most enthusiasm that I’ve experienced.

There are some states, towns, or counties that have been hit harder. That makes me more interested. In New York State, where I live don’t necessarily have the most deaths but we have a large population of people, our potential reach and impact can be greater around the topic. How have students responded? Students who maybe went to school because they wanted to work with athletes, do plyometrics that is healthy people, and they’re coming out, they’re like, “I had no idea that I’d be working with people who potentially were trying to find alternatives for chronic pain and tapering off of an opioid.” How have they reacted to some of this information when you work on the training with them?

I’m going to jump on that for a second because I have been so impressed with how the students have responded and I’ve also heard a lot of personal stories from students that have hit it home. Several students came to the training and said, “We keep Narcan in the house because I have a sibling. I have a relative. We know somebody in our family.” These are a lot of students from Massachusetts and Massachusetts hit hard. We had a few students who, through their undergraduate work, were already engaged and doing work around the opioid crisis. For the students, the idea that this comes into physical therapy was new to them, but the idea that we need to pay attention to the opioid crisis was not new and they will open to it. That’s my experience, Amy, I’m not sure if you had something.

I have a little bit of a different experience. These are students that maybe weren’t exposed at all to opioids or opioid use disorder as something that might be involved in physical therapy. The thing that’s been most poignant to me is their willingness to talk about their naivety. Thinking about how are we addressing those social stigmas by starting with our PT students. As healthcare professionals, everybody’s going to come in with their biases. You need to be able to know what your biases are in order to address them. This gives students an opportunity to confront something that they might not otherwise have.

You are targeting students. You’ve got something in a journal. You’re starting to target the education community, people who are interested in this, both in PT and outside of PT. How do you start to take this and get your peers, professors at DPT programs and maybe other programs around the world to start to pick this up and start to implement it into their program? As we know, it can be a long time before the research starts to change education and then change practice patterns?

We thought journal publication start to push this to a wider audience. Once it got published in the journal, we’ve shared it with some people at APTA who have expressed interest in and pass it on to other groups that are working on pain science and opioid issues. We’ve shared it with some other professional organizations that they can also take a look at it. The Massachusetts APTA chapter has a copy of it and it’s disseminating it. It’s about that little spider effect. It’s going to get legs and it’s going to start to march around hopefully. What we look for is to see the effect by people tweaking their programs a little bit and making sure they’ve got sufficient education so that the next cadre of clinicians o graduate are ready for at least this part of this public health crisis.

Is there anything you’d like to add to that, Amy?

There’ll always be room for two little people at a conference to continue to do the work. Having the information out there will hopefully make it a little bit easier. This is a topic that could be dismissed unless there are people that are willing to champion it. I would encourage people that are interested to continue champion it and not to hesitate to reach out to Julia or me.

It’s an important topic especially physical therapists in the United States. We’re one of the countries that are hit the hardest by the opioid epidemic. There are physiotherapists and other professionals around the world that are going to be interested in reading about these core principles that you’ve applied to physical therapy that can also be applied to other professions. Julia and Amy, you’re doing incredible work, which is why as soon as I saw the paper pop up in my news feed, I was like, “I have to invite them onto the show as soon as possible. I’m going to release this as soon as possible because it’s important to work.” First, Julia let us know how we can reach out to you. Where you teach and how we can learn more information?

I’m at Springfield College in Springfield, Massachusetts and you can email me at [email protected] and there’s a website that I keep. I’ll have links on that website ultimately to the core principles document, which is also up on the web. There are plenty of ways to find me. Find me on Twitter, on Facebook or wherever. I’m happy to share the information.

Amy, would you tell us wherever how we can find you?

When Julia and I started this project, I was in Boston at Simmons University. Since I’ve left Simmons and now, I’m at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, another area that has been hit hard by the opioid crisis. I’m super happy to be here and sharing this work and you can reach me at [email protected].

I also give you the free download that includes the link to The Core Education Principles that you two have typed up that professionals can download and they can access it. I’ll share the link to that website as well so everyone can access it. I had been speaking with Julia Chevan and Amy Heath, two doctors of Physical Therapy and educators who’ve done some amazing work around Core Education Principles with regards to the opioid crisis. If you’re reading to this blog, make sure to share it out with your friends and family on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and a Facebook group. Share it with your colleagues at universities. This is an important work that the United States of America would like to see the spread and go further. It’s been a pleasure being here with each of you and we’ll see you next time.

Thanks.

Important Links:

- Julia Chevan

- Amy Heath

- Developing core education principles for rehabilitation professionals in response to the opioid crisis: an example from physical therapy education

- ChoosePT Campaign

- [email protected]

- Twitter – Julia Chevan

- Facebook – Julia Chevan

- [email protected]

- @HeathAmyE – Twitter

- @JChevan – Twitter

- https://www.JChevan.xyz/

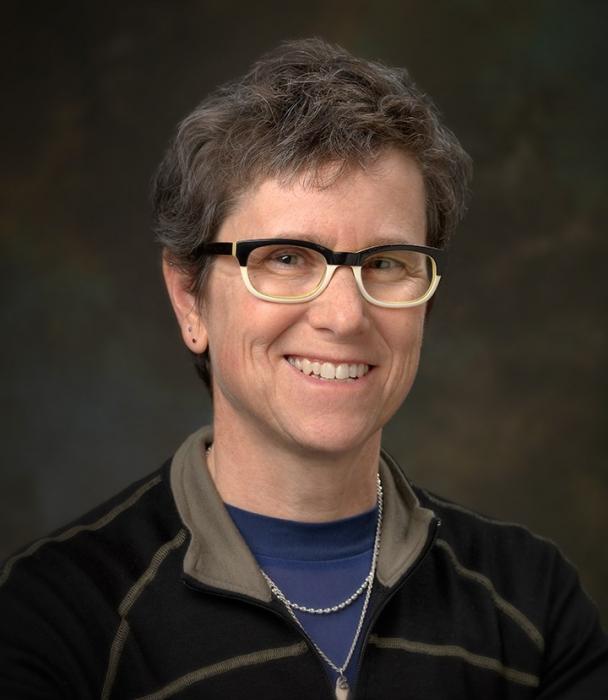

About Julia Chevan

Julia Chevan is a Professor of Physical Therapy and Chair of the Department of Physical Therapy at Springfield College in Springfield, MA. Her academic credentials include a BS from Boston University in Physical Therapy, an MPH in health policy and management from the UMass, an MS in orthopedic physical therapy from Quinnipiac University and a PhD in health-related sciences from Virginia Commonwealth University.

Julia Chevan is a Professor of Physical Therapy and Chair of the Department of Physical Therapy at Springfield College in Springfield, MA. Her academic credentials include a BS from Boston University in Physical Therapy, an MPH in health policy and management from the UMass, an MS in orthopedic physical therapy from Quinnipiac University and a PhD in health-related sciences from Virginia Commonwealth University.

She is ABPTS certified in orthopedic physical therapy and was a member of the first Educational Leadership Institute Fellows class (along with Amy Heath, her co-author).

About Amy Heath

Amy Heath PT, DPT, PhD is an assistant professor in the Department of Physical Therapy. Prior to joining the faculty at WMU, Amy was an associate professor of practice and program director/ chair of the Department of Physical Therapy at Simmons University (Boston, MA). She was also formerly an assistant professor and director of clinical education at Temple University (Philadelphia, PA).

Amy Heath PT, DPT, PhD is an assistant professor in the Department of Physical Therapy. Prior to joining the faculty at WMU, Amy was an associate professor of practice and program director/ chair of the Department of Physical Therapy at Simmons University (Boston, MA). She was also formerly an assistant professor and director of clinical education at Temple University (Philadelphia, PA).

Dr. Heath received her BS in Health Studies and Doctor of Physical Therapy degrees from Simmons College. She was certified by the American Board of Physical Therapy Specialties as an Orthopedic Certified Specialist (2007-17) and is an APTA Education Leadership Institute Fellow. Amy has worked with pediatric and adult patients in various orthopaedic settings and values the patient/PT relationship as integral to individualized care.

Dr. Heath is the author of several peer-reviewed articles, book chapters, and abstracts in the areas of education and admissions of DPT students, and evaluating DPT program quality. More specifically, her interests are in self-directed/ self-regulated learning, self-efficacy, learning strategies, and holistic admission procedures. While not yet practicing clinically since joining the WMU faculty, Dr. Heat’s areas of clinical interests include orthopedic conditions in adult and pediatric populations.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join the Healing Pain Podcast Community today: