Welcome back to the Healing Pain Podcast with Rachel Zoffness, PhD

We’re discussing how to bridge the gap between the mind and body in Pain Management and Pain Medicine. My expert guest is Pain Psychologist, Rachel Zoffness. Rachel is a Practicing Clinical Psychologist and an Assistant Clinical Professor at the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, where she teaches Pain Education for medical residents. She serves on the boards of the American Association of Pain Psychology, the Society of Pediatric Pain Medicine, and as a 2020 Mayday Fellow. In this episode, we’ll discuss the essential role of Pain Education, how health providers of different disciplines can use Pain Education in practice, and how to apply the Biopsychosocial Model Framework for the treatment of chronic pain. Let’s begin, bridge, or eliminate that gap between the mind and body. Let’s meet Dr. Rachel Zoffness.

—

Watch the episode here:

Subscribe: iTunes | Android | RSS

Bridging The Gap Between Mind And Body In Pain Medicine With Rachel Zoffness, PhD

Rachel, welcome to the show. It’s great to have you on.

Joe Tatta, thanks for having me.

I’m excited to chat with you about all things pain, dig into some of the nitty-gritty of where we are, how far we’ve come, how far we still have to go, both in our healthcare professions, all of our healthcare professions that are treating pain, as well as what we need to do to help people cope with pain out in the greater world. Let’s start here. What are we not doing in the realm of Pain Management that we should be doing to help people?

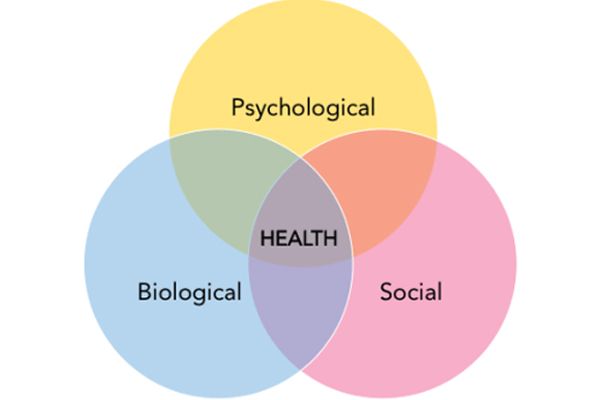

Where to even begin? The biggest problem that we have in pain is that we’ve erroneously framed it as a biomedical problem for many decades. By that, we framed it as a purely physical, mechanical, anatomical problem. What’s amazing and astonishing about that to me is that you don’t even have to dig very far in the literature to see that for many decades, science and neuroscience reveal that pain is biopsychosocial. All the theories of pain, all of them as far back as the Gate Control Theory in the ’60s, point out that thoughts, beliefs, emotions, coping behaviors, social factors, and contextual factors all implicitly affect the pain that people feel. For some reason, when we treat pain, and this has been going on for decades, we treat it as a purely biomedical problem with biomedical solutions. We throw pills and procedures at pain all day long. It doesn’t matter the age of the patient and their diagnosis. I know I’m preaching to the choir here, but it’s not working.

Incidents of chronic pain are on the rise. We’re in the midst of an opioid epidemic, which is getting worse during our pandemic. We’re seeing spikes in pain and opioid overdoses. It’s an absolute disaster. What are we not doing? We’re not framing pain accurately. If people like you and I had billion-dollar budgets like Big Pharma, we could probably bet that pain would not continue to be framed as a biomedical problem, but we don’t. The psychosocial treatments for pain are stigmatized. They’re not popular. They’re seen as treatments that are only for people who are crazy, or only for people with pain who have comorbid anxiety, trauma, and depression that’s not accurate. What’s happening with pain is that it’s a biopsychosocial problem. There are these three domains, but we’re only targeting one of them. Literally, we’re missing two-thirds of the pain problem.

How do you explain? The word biopsychosocial has been used on this show thousands of times. I use it all the time. I had someone on here and he said, “We need to scrap the entire word biopsychosocial because it doesn’t accurately explain what’s happening with regard to pain.” I’m not sure we want to get into that on the show now. How do you describe biopsychosocial? Let’s take health professionals first. Not all health professionals have Pain Education or Pain Training as part of their curriculum. In fact, those that may be perceived at the top of the food chain in the medical world, namely physicians, have some of the lowest rates of Pain Education and Training in their medical training. The public may have a different perception of what’s happening. I know you do some training with physicians. How do you explain what biopsychosocial means to a physician with regards to chronic pain?

I am so curious to hear the argument for why we need to scrap the term biopsychosocial. I personally think it’s wonderful and very helpful. The reason why I like it is because it offers a more comprehensive, all-inclusive picture of what’s happening with a human being. In the center, it doesn’t matter what you have in the middle of that Venn diagram. It can be cancer, anorexia, depression, or pain, it doesn’t matter. All human health problems are this thing that we call biopsychosocial. The reason I love the term is because you can easily try it out and explain what it is.

You’ve got the biomedical domain of the thing. In our case, we’re talking about pain. That’s a lot of things. It’s genetics, tissue damage, system dysfunction, anatomical issues, sleep, diet, and exercise. All those things are critically important for pain. No one would argue that they’re not. You’ve got the psychological domain of pain. When people shorten it, sometimes they just call it the psycho domain of pain, which is one of my big pet peeves. You don’t want to amplify the stigma anymore. We should do away with psycho maybe. The psychological or the psych domain of pain is thoughts, beliefs, emotions, coping behaviors, and even past pain memories. If you do research or look at the research on pain memories and the role of the hippocampus in pain, it’s huge and wild. To pretend that thoughts and beliefs about your body and pain don’t affect your experience of pain is ridiculous. The research is many decades old.

You’ve got the sociological domain of pain. That’s your family system, larger context, race, ethnicity, religion, community, and larger environmental context. Of course, we know that also impacts the pain you feel. To say the pain is not biopsychosocial is purely biomedical. We know that’s wrong. To not use that term, I’m not sure what people would recommend replacing it with. I’m all for using a term that’s easily digestible. People are great with visuals. The biopsychosocial bubble thing works well. When I do trainings, I’ve never had anyone not get it.

I use it with kids in my office as young as eight. I find it to be very descriptive. I usually have people tell me what they think their biopsychosocial is, the triggers are the things that hurt and the things that help their pain. It’s a great descriptor of what’s happening. I’m teaching med school at UCSF. The physician trainees are all-in. This next generation already know and believe that all health is biopsychosocial. This is not new information. When you give them a term, then they try it out and teach it to their patients. It’s a useful tool for framing health problems.

For those of you who want to explore it a little bit deeper with regard to the biopsychosocial model and alternatives, you can check out the interview with Peter Stilwell. He’s a pain researcher. One of the criticisms of the biopsychosocial is that it rolled out in a nice way in the research many decades ago. Somehow, as those three spheres were rolling out, they got separated into a bio, psycho, and social. Within those columns or three spheres, if you will, we then have the deconstruction of that model that has happened in certain places within our healthcare system and, at times, within a practitioner themselves.

One of the things that I am so passionate about teaching professionals is you don’t have to work in a multidisciplinary clinic to provide biopsychosocial care. There are ways that you can achieve that yourself through professional development and working with patients to integrate the type of care into your clinic. That’s the one concern. There’s not an embodiment of that model, either in our healthcare system, in our individual practice, and by those at large.

Two things, I agree 100%. Thing one is, is the problem that we’re calling it a biopsychosocial issue that is pain. Is that the problem? Is the problem that the way we treat human beings in Western medicine is broken? I will humbly submit that the word is not the issue. I agree with that perspective. When I get on my soapbox, one of the major problems we have with pain is that we are all siloed in our separate disciplines. We’ve got a PT over here, OT over here, Psychology over there, Anesthesiology over there, and Physiatry over there. We’re all treating the same patients and the same issue at the end of the day. Collaboration is not happening sufficiently.

Part of the problem in my mind is that, in Western medicine, people either have physical pain and they see a physician and maybe a PT if they’re lucky, or they have emotional pain and they come to someone like me. I’m a pain psychologist. We know that’s not how pain works. It filters through the brain’s limbic system, your emotion center, 100% of the time. Pain is always physical and emotional. We have this problem in Western medicine. We’re artificially dividing and funneling people down these separate pathways, when in truth, that’s not how pain works. I’m not sure the problem is the term, but I am open to all suggestions. We’re definitely doing a lot of things wrong. If someone has a better idea and a better term, bring it. I’m all in. At the end of the day, we all need to be collaborating, talking, doing stuff like this, having conversations, and moving the needle. That’s what needs to happen. I don’t know if the word is the problem necessarily.

You mentioned stigma around the treatment of pain. There are lots of stigmas attached to pain in many different aspects and included in the biological, psychological, and social. The psychological perhaps sticks out a little bit more. We know that chronic pain is not a psychological disorder. We know that mindset is very important with regard to treating pain. When a patient first approaches you or they’re tiptoeing around the idea of seeing you, how do you describe what you do in a way that destigmatizes treatment for them?

There are so many things I want to address about the thing you just said. Yes, there is a ton of stigma around people living with chronic pain. Yes, there is a lot of stigma around this suggestion that pain is chronic pain. It’s somehow like a psychological disorder or any comorbid anxiety. Anxiety or depression is a sign that people with pain have a mental illness. Totally, 100%. There’s a couple of different things that I do. One is that I tell people who are referring to me to call me a pain coach. I see patients of all ages. My favorite age group happens to be the teen, tween, young adult groups, but I see older adults and younger kids. The way I pitch it to everyone, patients, and providers alike is that, if it is okay to go to a soccer coach to get better at soccer, it is surely okay to go to a pain coach to get better at dealing with pain. Pain is hard to deal with and everyone living with pain deserves support.

That takes some of the sting out of it. There’s no way that I am going to be able to pull the stigma out of seeing a psychologist a “mental health professional” and someone who treats physical pain versus emotional pain. I’m not going to be able to remove that stigma on my own of seeing a psychologist for a physical problem. However, using the pain coach language is helpful. That’s thing one. Thing two is I like to remind patients and providers alike that when we see signs of stress, anxiety, and low mood in our patients, that is natural and normal. It’s what we call a normal response to an abnormal situation. For example, if there were a pandemic and you had no stress and felt 100% calm all the time, that would be weirder. Of course, you feel stress and anxiety with a situational trigger like a pandemic. It’s the same with chronic pain.

Pain is one of the biggest stressors on the human body. Moving across the country is a stressor. The death of a loved one is a stressor. Being in pain all day every day is a stressor. Of course, you have anxiety and depression when you’re living with pain day in and day out. Your body is not built to be in pain for months and years. When you lose your social life, sex life, and ability to engage in hobbies and pleasurable activities, your mood crashes. Your stress and anxiety system activates. I am of the mind. I get to say this because I’m a psychologist. That is not truly a mental illness at all. That’s a normal response to an abnormal situation.

What I see with my patients is that when we treat their pain in a biopsychosocial framework, anxiety and depression go down, functionality increases, and that “mental illness thing” magically resolves. There are ways of talking about it. The problem is that we don’t talk about it. We don’t talk about the stigma, and we should all be doing that upfront. People will be referring more to psychologists, biofeedback, and these other psychosocial treatments. Hopefully, they’ll be doing it in a way where they say to their patients, “There might be some stigma around this for you. I just want to say upfront, I don’t think you’re crazy. I don’t think it’s on your head. I don’t think you’re faking it. I don’t think you’re making it up.” That conversation needs to be had because so many patients report getting that message, either overtly or interpreting it that way.

What’s your opinion on physical therapists and other licensed health professionals using principles of psychology in their practice? If they are, how can they overcome the potential cognitive dissonance that happens when a patient comes to them? For example, if you come to see a physical therapist, you may expect exercise and physical activity. You may not expect that, “In addition to that, we’re going to do a little mindfulness exercise.”

I had a feeling you were going to ask me that. That’s an important thing for us to talk about, too. Here we are talking about our silos, PTs to the left and psychologists to the right, and medicines down the hallway. This is my humble opinion. You’re asking me for it. I do, of course, think it’s important for us to stay within our professional boundaries. I would not perform surgery. That would be insane. However, I absolutely 100% think it’s appropriate and important for physical therapists to be using some of these strategies. You guys are pain coaches just like I’m a pain coach. I bet there are things that you’re doing that I can and should use. In fact, I do pacing with my patients, which is something I pulled from the PT literature.

I use PT stuff all the time like Lorimer Moseley and Adriaan Louw, two of my pain science heroes. I definitely think that PTs can and should be using some nuggets from Pain Psychology. Do I think that PT should be calling themselves mental health providers? No, that’s not appropriate. Do I think that PTs should go around saying like, “I can give you an entire course of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy?” Probably not. If you’re not licensed to do it, you probably can’t do a whole course of CBT. Can you use strategies? Absolutely. Should you? In my opinion, yes. Sometimes your patients are not going to get to see a pain psychologist. I’m all about having a tool belt with as many tools as you’ve got and offering your patients things that might help them. They get to decide what they implement and use. Yes, use mindfulness. Use some cognitive strategies, behavioral strategies, and behavioral activation. Use that stuff. I use your stuff. You should use mine.

The flip side of that would be as we’re breaking down silos rapidly during this episode, how do we encourage mental health professionals to use physically informed psychology?

Say that differently.

As you all know, the literature has grown with regard to physical therapists, adopting principles of psychology in their practice. That makes a physical therapist practice multimodal. In essence, we’re taking interventions that maybe only have minimal results and outcomes. When we combine them, we’re more likely to get moderate and maximum effect sizes. Knowing that exercise is powerful pain medicine and not only helps physically, but also helps psychologically and emotionally. In all those three spheres that we’re talking about, biological, psychological, and social, how do we encourage psychologists?

I’ve had these conversations at a couple of meetings I’ve been to with a psychologist president. Sometimes it goes over well. Sometimes it does not go over well at all. Maybe I should come out and say it. I know, Rachel, you and I are on the same page with these things. The idea that seeing a patient who has a problem with physical function and only sitting and talking to them twice a week for 8 to 14 weeks, are we then not helping them with the behavioral activation that they need and the exposure that’s required for them to take it out of the therapy room and place it into their life?

Two things about that. One is that, I sit here all day and talk about how Pain Education is lacking across disciplines and how 96% of medical schools in the United States and Canada have zero dedicated, compulsory Pain Education, which blows my mind. One of the biggest offenders is Psychology. I’m a Nerd. I was in school for 40 billion years. Luckily, as an undergrad, I had the best neuroscience class at Brown. We talked about pain. I ended up doing my honors thesis on pain and going down the rabbit hole. I was so fascinated by it. In the years, since I got two Master’s degrees, a PhD in Psychology, an internship, and a postdoc, this thing of physical pain did not show up again until my postdoc. It was only because I was all about it and I wanted to go down that rabbit hole.

In general, psychologists are not trained in pain at all. They are not trained to bridge this gap between physical and emotional, to bridge the gap between Medicine and Psychology. That’s also true in many Health Psychology programs. There are some Pain Psychology programs, but there are very few. The answer is that we need to train more mental health professionals, not just psychologists, but social workers and MFTs in Pain Science. That needs to be part of every program. As you know, patients who show up with anxiety, depression, or trauma, emotions don’t live in your head. They also come out in your body. All of these “mental health conditions” have physical components. All therapists, in my very humble opinion, which is also a very strong opinion, should be trained to address pain and somatic symptoms. That would be a more integrative provider is what you’re saying. That’s thing one. Yes, we need more training in Psychology.

In many ways, what you’re saying is that cognition is embodied, which helps if we’re along the same line here. When I say cognition is embodied, it helps us remove the idea that cognition happens from the neck up when your nervous system is not just your brain. Your nervous system is your entire central nervous system, peripheral nervous system, sympathetic, parasympathetic, etc., which is throughout your entire body. If you look at cognition being embodied, then we have to treat the mind as well as the body no matter which type of practitioner you are.

The best way I’ve found to teach that, by the way, is a little thing called biofeedback, which I’m obsessed with and used in my practice. In biofeedback, you sit in a chair. If you’re me, a very nice and elderly biofeedback provider will tell you that he is going to teach you to warm your hands to 90 degrees. If you’re me, you say, “I am a scientist. I do not believe in voodoo.” While you’re hooked up to this machine, you are watching. He will use techniques. You’re thinking certain thoughts, like particularly stressful thoughts. Your hand temperature, for example, will plummet. Muscle tension in your body will spike. You’ll be like, “The things I think in my head are inherently, inextricably linked to the sensations and things that are happening in my body.” In two sessions, you’re able to warm your hands to 90 degrees. It’s pretty magical. Biofeedback is great.

The thing I was going to say is that CBT, which is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and not CBD, sometimes people think I’m talking about medical marijuana. I’m not. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is my ace in the hole when it comes to treating chronic pain. I find it to be incredibly, hugely effective, and useful for my patients in part because it’s teaching tools for pain management and skills for life. In part, because it is making this connection between brain and body, between thoughts, emotions, physical sensations, and pain. It’s offering patients a modicum of control over their bodies and brains.

In CBT, to your question, I have my patients pick a thing that they want to do during the week. It’s like, I try not to use the word homework because people would never talk to me again. It’s the thing that happens in the spaces between. I get people once a week. What happens in the space between? The thing that I’m often recommending is something that’s physical in nature. You walk around the block or whatever it is. It’s part of their pacing planner. To your question, how do you link the two things? You train more mental health professionals, social workers, marriage and family therapists, psychologists to be integrating treatment for pain medicine into any psychologically informed approach. We shouldn’t be so separated and siloed because then we’re not practicing biopsychosocial medicine, which is exactly what I think you’re saying.

You’re a big advocate of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy?

Yes.

You mentioned that you see huge benefits for people in your clinical practice when you use it. There was a psychologist who is primarily a researcher. She’s on two Cochrane Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis on CBT for pain specifically. Her outcomes are the same in both. The reason I’m asking is I’ve got a number of questions from readers on the show. Her results said that CBT has minimal or minimum effect sizes and outcomes for people living with pain. If you’re someone who has pain, you might think in your head, “There’s minimal, moderate, and maximum.” If you’re someone in pain, you’re like, “I want to find the person who has the maximal results. I don’t want this minimal type of stuff here. I’m in pain. I’ve been suffering for a long time. It’s taken me a long time. Finally, someone has now recommended something for me and you’re telling me it’s minimal?”

I have an answer for you. I think about this a lot. I think about this as a provider, as someone who has lived with pain, as someone who is a nerd and reads research all day long for many years. What we learned in our very dorky, research-based PhD program was that when you’re reading research, you never just look at the conclusion. You always look at how the research was done. When you’re comparing research studies, especially meta-analysis, you want to look at what’s being compared.

I’m going to give you some issues that I personally have with the CBT literature.

I love meta-analysis, by the way. They’re very helpful. I also think we need to research the research that we’re reading before we come to any conclusions. If you look at the papers that are included in the meta-analysis, there is no one standard operational concrete definition for CBT. You ask ten different people, you will get ten different answers. There’s not one manual that everybody is using. Everybody is using a different manual and different strategies. There’s no operational definition. What are we measuring when we talk about CBT? That’s problem number one.

Problem number two is, what is the length of treatment? One study has it for eight weeks via an online virtual treatment platform. Another one is doing twelve weeks in-person. The length of time is not standard across studies. Thing three, who is the provider providing the treatment? In some research studies that I’ve read, it’s some unsuspecting grad student who has signed up to work with a researcher, and they’re suddenly saddled with providing some treatment they’ve never done before. In other studies, it’s a social worker. In other studies, it’s a seasoned pain psychologist. What we know from the psychological literature and the pain literature is that the provider matters. There are all these provider factors that feed into the treatment efficacy.

We’re never comparing apples to apples. What we can say about Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is that if you break it down into its component parts, there’s abundant research that supports each of the component parts, which is how I go about CBT. Cognitive strategies for pain are effective. Behavioral strategies for pain are pretty effective. Exercise for pain is effective. Pain education, which I’m obsessed with, is also effective. If you look at the component parts, biofeedback and mindfulness for pain, which is part of what I do, there are all these different parts. It depends on the recipe that you’re using. I balk whenever someone says to me, “This paper says that CBT for pain is super effective, and this paper says it’s minimal.” I’m like, “What are we measuring?” We need to come up with some operational definition of CBT before we can pretend we’re measuring something. It’s like some CBT soup out there. I don’t know what anybody’s measuring. It’s certainly not consistent across studies.

I asked her that question. As you mentioned, CBT can be 7 to 10 to 14 sessions. I asked and said, “How much of that CBT also included lifestyle-type interventions like sleep and nutrition?” Sometimes those are part of a longer CBT intervention. Sometimes they’re left out because it’s not a pure cognitive approach or modeling. I think the right answer is, if she were to go back and look at those studies, if we were to backlink those studies, sometimes they mentioned them in the actual paper, but 99% of the time, they don’t.

You and I should write an article about that.

The other thing that came up in that paper was there was a commentary about ACT, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, for chronic pain. The conclusion of the paper was that the CBT literature has more evidence. We should stick with that and wait for the evidence on ACT to build. A lot of people follow this show because we talk about mindfulness, ACT and everything on this show. They asked me, “What do you think about that? What do you think about ACT? Do you teach ACT?” I’m curious from your perspective what are your thoughts on that.

I always go back to the thing where I feel like what I want to do most is offer my patients as many tools as I can that I have personally vetted. I’ve gone down the rabbit hole. I’ve read the things. I know it’s not hooey. It’s not pseudoscience. It has some evidence. At the end of the day, the best thing we can do is offer some strategies. If it doesn’t take, it doesn’t take. There are some of my clients that hate mindfulness. I get it. That’s fine if it’s not your thing. For some of my clients, it changes their life, helps them get out of bed, and face the day. Yes, let’s try ACT with our patients. I literally can’t think of a reason other than that. Yes, there’s not a fund of literature, but it’s not like a pill where if you take it, your liver might fail. The side effects of trying ACT with a patient are minimal, if any. I feel like we don’t have that much to lose and a lot to possibly gain. Yes, let’s disseminate tools and resources if we have them. I can’t think of a great reason not to.

It’s also interesting to me because a lot of those cognitive behavioral interventions have mindfulness as part of them. Mindfulness is oftentimes a trait or implicit in some of the things that we’re doing with people, whether you’re coming from a very traditional cognitive behavioral or a more third wave type interventions. It’s interesting that doesn’t show up as you mentioned in the literature, either. Even breaking things down into mindfulness versus ACT, there are these processes. There’s diffusion or decentering. There’s so much. As you mentioned before, there’s an alphabet soup that happens after a while.

The thing about ACT is that it’s an offshoot of CBT. It grew out of CBT. There’s a lot of overlap. At the end of the day, this thing that we’re calling Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, in my mind, especially for pain, is an amalgamation of a lot of different things that we’ve found to be effective back to the thing we were saying before that. There are cognitive strategies that have been shown in the literature to be helpful for pain because your cerebral cortex and prefrontal cortex impact the pain you feel 100% of the time. Let’s change those brain structures to help your pain. At the end of the day, what we’re doing is this little thing we call neuroplasticity. We’re changing the brain to change the pain. If you don’t do that, nothing’s going to change.

The body is important, too, which is what you’re talking about doing pacing and involving PT. CBT becomes this mishmash of all these different pieces of the puzzle. The lifestyle component of CBT is one of the things that I ended up going after first. I have a dorky sleep hygiene handout that I give to everybody, especially to my teenagers. They’re up until 4:00 in the morning and sleeping until 2:00 in the afternoon. It almost doesn’t matter what we call it. I’m up at Dartmouth now. I’ve started consulting here, believe it or not. I met this wonderful pain neuroscientist. His name is Tor Wager. I love his research. You’ve probably read it.

He and I were talking. There’s another therapy that’s being developed now that is, in my mind, exactly the same as CBT. It maxes almost one-to-one. The problem is that we don’t have operational definitions for the therapies we’re using. That’s problem one. Problem two is that people are so territorial about the names of things. It either has to be accurate, has to be CBT, or has to be this new. At the end of the day, we’re all doing the same thing. We’re providing Pain Education. We’re helping patients change their thoughts. We’re helping them engage in healthier behaviors and break unhealthy habits. We’re helping them have a healthier lifestyle. I don’t care what we call it at the end of the day. It seems like we’re all doing the same thing.

When I interviewed Lorimer, you mentioned Pain Education. I’ve been a PT for a long time before the Pain Education phenomena that we have now. We were still doing Pain Education back then. We didn’t necessarily have a word for it. There are multiple types of cognitive behavioral therapies. I asked him during the interview because I haven’t heard him or other professionals say this, “Is Pain Education a form of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy? Have you taken it to that place yet?” He, very intelligently, turned it back on me and said, “Did you learn about Cognitive Behavioral Therapy when you were in physical therapy school?” I said, “No.” I went to PT school in 1995. That wasn’t on the radar at all. It probably wasn’t even on most pain psychologists’ radar at that time. He started that. He did arrive at the place where Pain Education is a form of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy because you’re helping people with their thoughts and beliefs and how it relates to their behaviors and physical outcomes after that. When you look at Pain Education, does that fit something that CBT or ACT hasn’t been able to address? As I mentioned, we have been doing this. We just now have a fancy name for it.

If I remember correctly, Lorimer wrote a paper on why Pain Education is not CBT. He had some very strong language around that. I’m going to need to go find that. There was a table. I asked him that also. I do think that there’s a difference. I don’t care what we call this thing, but the thing that I’m doing, what I’m calling it is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. It doesn’t matter at the end of the day. One of the most important components of CBT is Pain Education. For me, that comes first. I don’t do anything else with any patient until they understand their pain. Why? Pain is a ubiquitous human experience. Every patient and every provider should understand pain.

It’s never taught. It’s not taught in doctor’s offices, med school, and PT school. Most of the time, it’s not taught in Psychology programs. It’s the first thing I teach. Pain Education to me is the foundation for everything else. If you don’t understand that your cerebral cortex, thoughts, limbic system, and emotions impact that we’re calling this physical experience and pain, then at the end of the day, you’re not going to buy into what Joe Tatta and Rachel Zoffness are doing. You’re not going to buy in. In my mind, the Pain Education piece has to come first. There are a lot of other things that grow from there. A very big part of what I’m doing is being a private detective. At any given moment, I’m trying to figure out the biopsychosocial puzzle of the person sitting in front of me. What are the contributing factors to their pain? Certainly, there are biomedical contributors. Those are the things 9 times out of 10 that have already been treated, medicated, and surgery.

There’s the whole psychological domain. What are their thoughts and beliefs about their body and pain? What are their past pain memories? What’s going on with their trauma, anxiety, and stress levels during a pandemic in particular and their mood? How has that felt feeding the pain that they’re experiencing? What can I do to help them with that? The social or sociological domain of pain, it’s the same. What are the family factors and the contextual factors that are amplifying the pain that they’re feeling? CBT is a lot more than just Pain Education. I don’t think that’s sufficient. Pain Education is critically important, but I don’t think it’s sufficient.

When you’re using CBT, do you just have 1 or 2 sessions dedicated to that? Does that become a through-line that happens throughout the entire treatment with the patient? Is it more in the beginning and then tends to wane as you see that people have an essence reconceptualized? How do you approach that?

I said this before. I’m a huge advocate of Pain Education. To that end, I’m always trying to think of language, words, and ways of framing pain and neuroscience that are going to be impactful and helpful. I have to admit I do this selfishly, trying to think of ways that I can explain the pain that will increase buy-in and motivation to try these treatments that are so helpful. If a patient does not know that their thoughts and emotions amplify or decrease their pain, they’re not going to do anything I’m suggesting. Pain Education is a thread throughout. It begins at the beginning. The beginning sessions are always Pain Education heavy. It goes through the entire course of treatment. With some patients, it’s six sessions or whatever. With some patients, it’s six months. It depends on the person who’s sitting in front of me.

I always offer a metaphor. This is the metaphor I always use with anyone who comes into my office. It’s the thread throughout all of our treatment. I want you to imagine in your central nervous system, that you have a pain dial. It’s like the volume knob on your car stereo. The pain volume can be turned up and turned down by lots of different factors, three in particular. One is stress and anxiety. One is mood. One is attention or what you’re focusing on. There are lots of factors that amplify or decrease pain volume, but three in particular. Here’s how this works. When stress and anxiety are high, your body is tensed, and tight, and your thoughts are worried, your brain sends a message to your pain dial, turning pain volume up. Pain feels worse when stress and anxiety are high.

Number two is mood. When mood is low, you’re miserable and depressed, and emotions are negative, your limbic system sends a message to your pain dial, turning pain volume way up. Pain feels worse when mood is low and emotions are negative. Thing three is attention. When you were in bed focusing on your pain, not going out, not doing anything, and not engaged in life, your prefrontal cortex sends a message to your pain dial, amplifying pain volume. Pain feels worse when you’re focusing on it. The opposite is also true. This is so important for people with pain to know. No one’s ever told them this before. When stress and anxiety are low, your thoughts are calm, your body and muscles are relaxed, your brain sends a message to your pain dial, lowering pain volume. Pain feels less bad when stress and anxiety are low and when you’re managing it.

Thing two is mood. When your emotions are positive, you’re happy, you’re engaged in your life and in pleasurable activities, your limbic system turns down your pain dial, lowers pain volume. Pain feels less bad when your emotions are positive. Three is attention. When you’re distracted, when you’re engaged in your life and you’re out doing things, you’re with friends and you’re moving your body, your brain will lower your pain volume. Your prefrontal cortex turns down the pain dial. The reason I share that metaphor here and with my patients is because that gives me traction. From that moment on, every single session I ask my clients what they did that week to lower their pain dial every week. That becomes the thread of everything else. That’s the foundation. If they don’t know that there’s a pain dial that’s affected by thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and lifestyle choices, what do I have? How are they going to buy in? How are they going to take my advice?

Can I add a dial to your dashboard?

Totally.

Sometimes even with all that, for certain people at certain times of our life, depending on certain environments, sometimes those things may not work so well. We have control of the pain dial, but we also have another dial called willingness that we can control. Sometimes even when you have pain, you can still turn that willingness dial up, even in the presence of pain, if it’s towards something that is deeply meaningful, important, and that you love in life. You’re constantly adjusting these two dials. What about the biopsychosocial lifestyle factors and the behavioral change factors? Can I adjust on that pain dial? As I’m doing that and experimenting with this, how do I adjust that willingness dial and ratchet that up a little bit and know that this process might be two steps forward, one step back sometimes? Eventually, you’ll wind up at a place where the pain dial is lower and the willingness dial is higher.

I sometimes feel like my job is a motivational interviewer. That’s a lot of what ACT is also. I agree that values-driven behavior is critically important for everything, especially pain. A lot of our patients are dealing simultaneously with addiction and other issues. Motivational interviewing and willingness, that’s huge.

We didn’t get into the addiction aspect of it. Can we touch base on one topic with regard to addiction?

Sure.

It became apparent to me that we were ripping the carpet out from underneath people a couple of years ago when we decided to not refill prescriptions, aggressively taper when there was no need to taper, taper when the prescriber didn’t understand how to taper, or look at the biopsychosocial factors that are involved with tapering. What’s your advice to someone who potentially has been on an addictive substance? There are many of them. They’re thinking about tapering. They’re scared because they know that it’s difficult to find someone to help them taper down appropriately and to help them cope with what may happen during the taper.

Tapering is admittedly not my area of expertise. I don’t want to pretend that it is. The biggest problem in that realm is that we are tapering people off of their one pain treatment strategy without offering them others. There aren’t enough health providers out there trained in pain who can offer them replacement tools for their toolbox. You cannot say to somebody, “I know this is the one strategy you have for effectively managing your pain, but sorry, we’re going to take it away.” That’s so brutal and inhumane. If we’re going to tell providers to taper, we have to simultaneously train them to offer equally as effective strategies. Until we have an army of health providers trained in pain, which is something that you and I are doing, we cannot fairly ask people to be tapering and not using their pain management strategies that they found to be so effective. It’s unfair and inhumane. Have you ever read Drug Dealer, MD by Anna Lembke?

Yes.

It’s this quick, short read, but it is so wild. It outlines this history of treating pain with opioids and brings us to where we are now. Of course, Beth Darnall at Stanford is doing some great work in the opioid tapering space. It’s a real problem that we have that there aren’t enough healthcare providers across disciplines. We’re just tapering without offering replacement strategies. It’s wild.

Rachel, it’s been wonderful speaking to you. Lots of great take-homes for both practitioners and people living with pain. Let everyone know how they can learn more about you.

That thing where I said I was a nerd is true. I have a website. It’s my last name. It’s Zoffness.com. On it, I have a Resources page. I have it there selfishly for myself, but also for everybody else. It has books and links to other websites and podcasts, including this one. It has apps and it has a whole bunch of things. That’s a great way of finding out more information. I’m also on social media. I don’t love it, but during COVID, it has helped me connect with like-minded professionals who are doing work in the pain space. I am on Twitter. You can find me @DrZoffness. Tweet at me and we can be friends. I’m also on Instagram. @TheRealDocZoff is my handle. I’m on LinkedIn also. It’s just my name and on Facebook. I’m using all the social media stuff.

I’m like Dr. Tatta in the sense that it’s important to put Pain Education into the hands of providers and patients. To that end, I’ve written two workbooks. It’s important for us to not just only be the holders of pain information, but to be disseminators of information. One of the workbooks is The Chronic Pain and Illness Workbook for Teens. The only reason that was born was because I was looking for resources for myself and my patients and I could find none. There are great guides for therapists who want to treat pain, but there’s not that much for patients, especially not kids and teens. The Chronic Pain and Illness Workbook for Teens is out there on Amazon.

I’m also one of those people who advocates for pain treatment to be accessible and affordable. That’s a question that we didn’t get to. CBT and Pain Psychology are often not affordable for most patients. That’s so unfair. I put everything I do in my practice into a workbook. The workbook for providers and adults living with pain is out. That’s called The Pain Management Workbook. The Pain Management Workbook is on Amazon for something like $20. Dr. Tatta and I are just being the holders of the information. This information can go out and be used by any healthcare provider. Literally, any nurse, PT, OT, physician, social worker, therapist, or psychologist can use the workbooks and do some of these strategies. Like Dr. Tatta was asking before, are you allowed to step out of your comfort zone and use some nuggets from Pain Psychology? The answer is yes. That’s where I can be found.

Make sure to check out those resources. Of course, you can follow Rachel on social media. Check out her website Zoffness.com to access all the research resources she just mentioned. At the end of every episode, I ask you to share this with your friends, family, and colleagues on whatever social media platform you’re talking on. If you’re in a Facebook group, make sure you grab the link to this episode. Drop it in the Facebook group so practitioners or people with pain can access it. We’ll see you next time.

Important Links:

- Rachel Zoffness

- Peter Stilwell – Past episode

- Dr. Lorimer Moseley – Past episode

- Drug Dealer, MD

- @DrZoffness – Twitter

- @TheRealDocZoff – Instagram

- Rachel Zoffness – LinkedIn

- Rachel Zoffness – Facebook

- The Chronic Pain and Illness Workbook for Teens

- The Pain Management Workbook

About Rachel Zoffness, PhD

Dr. Rachel Zoffness is a pain psychologist and Assistant Clinical Professor at the UCSF School of Medicine, where she teaches pain education for medical residents. She serves on the boards of the American Association of Pain Psychology and the Society of Pediatric Pain Medicine, and is a 2020 Mayday Fellow. Dr. Zoffness is the author of The Chronic Pain & Illness Workbook for Teens, the first pain management workbook for youth, and writes the Psychology Today column “Pain Explained.” Her new workbook for adults and healthcare providers – The Pain Management Workbook – was just released and is now available on Amazon. Dr. Zoffness was trained at Brown, Columbia, UCSD, NYU, and St. Luke’s-Mt Sinai Hospital.

Dr. Rachel Zoffness is a pain psychologist and Assistant Clinical Professor at the UCSF School of Medicine, where she teaches pain education for medical residents. She serves on the boards of the American Association of Pain Psychology and the Society of Pediatric Pain Medicine, and is a 2020 Mayday Fellow. Dr. Zoffness is the author of The Chronic Pain & Illness Workbook for Teens, the first pain management workbook for youth, and writes the Psychology Today column “Pain Explained.” Her new workbook for adults and healthcare providers – The Pain Management Workbook – was just released and is now available on Amazon. Dr. Zoffness was trained at Brown, Columbia, UCSD, NYU, and St. Luke’s-Mt Sinai Hospital.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join the Healing Pain Podcast Community today: