Welcome back to the Healing Pain Podcast with

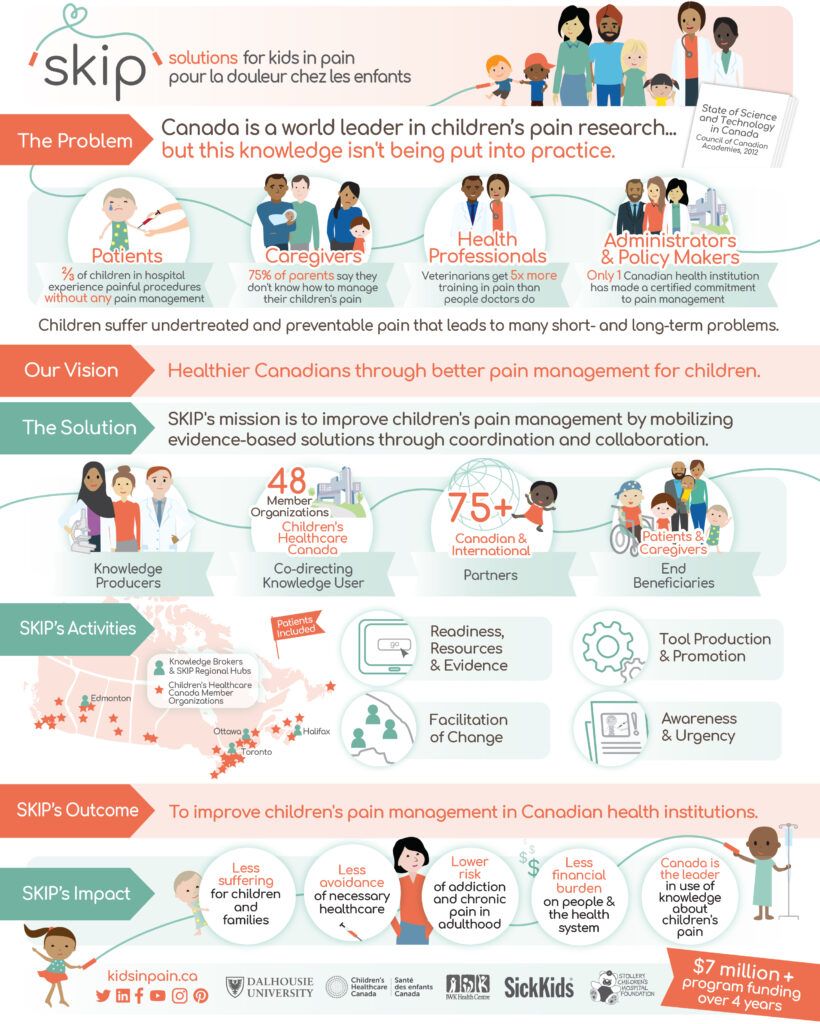

We’re discussing the important topic of how to improve children’s pain management. If you’re not aware of the lack of pain management that children or adolescents experience, it’s because it doesn’t receive a lot of attention. I want to share a vital statistic that our guest speaker shared with me. Did you know that more than two-thirds of children in hospitals experienced painful procedures with absolutely no pain management? They don’t receive any pain management. This includes pain management during routine vaccinations, while undergoing medical procedures, after surgery and in the context of chronic pain and chronic disease. Out of all the countries on our globe, Canada is a leader in pain research and children’s pain. Even though we have tons of books and information and research articles, one of the great challenges is that this information is not being placed into practice where practitioners can use it to help people with pain.

Joining us to discuss children’s pain and how to improve children’s pain management is Dr. Christine. Chambers. Christine is a clinical psychologist whose research is aimed at improving the assessment and the management of children’s pain. She has published over 150 articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals and was identified as one of the top ten most productive women in clinical psychology in all of Canada. Her Canadian Institute of Health initiative called It Doesn’t Have to Hurt, has generated over 150 million views worldwide, has trended on social media, has won multiple international awards and was featured in the New York Times. Dr. Chambers holds leadership roles in the International Association for the Study of Pain, as well as the North American Pain School. We’ll talk about Dr. Chambers’ project called Solutions for Kids In Pain or what is simply known as the SKIP Project, whose mission is to improve children’s pain management by mobilizing evidence-based solutions through knowledge, coordination and collaboration.

I enjoyed this interview with Dr. Chambers. I know you will too. We cover a host of topics with regard to child pain. We also touch base on important topics with regards to parenting a child with chronic pain. There are lots of great take homes for everyone, whether you’re someone with pain or whether you’re a clinician who treats parents or children with pain. I want to thank Christine for being here. She’s doing amazing work. Make sure you check out her websites and check out the great infographic that is included.

—

Watch the episode here:

Subscribe: iTunes | Android | RSS

Solutions For Kids In Pain: The Power Of Partnerships To Mobilize Research Knowledge For Children’s Pain Management with Christine Chambers, PhD

Christine, welcome. I’m excited to talk to you.

Thanks for having me.

We have touched on the topic of pediatric pain throughout the evolution of this. I first came across your work at World Conference ISP and then I started looking into your websites and started looking into your research and I said, “This is someone who I have to have on and people are going to be interested in some of the things you have.” You’re a psychologist. Tell us how you first became interested in studying pediatric pain.

Like a lot of things in life, it was purely by accident. I always knew I wanted to be a child psychologist. I read a book about a child psychologist when I was in grade six. From that point on, every year I would fill out in my little annual yearbook, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” I always wrote, “Child psychologist.” I didn’t understand the role that research played in becoming a psychologist before I got to university. When I met with an undergraduate advisor and said, “I want to be a child psychologist, what do I need to do?” He told me what courses I needed to take. He also said, “You’re going to have to do research so that you can get into a PhD program.” I was like, “That sounds interesting. What child psychologists do you have in your department?” He’s like, “We have one. He’s studying children’s pain management.” I was like, “That’s what I’ll be doing.” That’s how I started in the field as an eighteen-year-old undergraduate student. I connected with a mentor here in Halifax, Patrick McGrath, who was one of the fathers of the field of Pediatric Pain Research and had wonderful experiences. It’s a wonderful field to be connected to. I decided to stick with that research area throughout my career. I went on to do a PhD with a focus on Pediatric Pain in Vancouver, working with Ken Craig and have continued this research as a faculty member.

You’ve had roots in this particular topic since you’re eighteen. It’s so interesting because oftentimes psychologists may discover pain somewhere in a fellowship way long. You’ve been doing this since undergrad, which I think is incredible. You’re also Canadian. Let’s talk about pediatric pain first. How pediatric pain, the care of pediatric pain, is evolving in Canada versus the US or other parts of the world. We’re neighbors but our healthcare systems can at times be vastly different.

Pain that isn't treated well harms children's brains and bodies! Share on XThere are a lot of differences in our healthcare systems, and there are unique cultural issues that are present in any particular country that you’re looking at. Interestingly enough, I think the challenges are quite similar globally when it comes to children’s pain management, which is we have a lot of knowledge now. We’ve acquired a lot of scientific knowledge about how to better assess and manage children’s pain. It’s not to say that we’ve identified all the answers. There are lots of areas that where we still need to make a difference in terms of new knowledge. One of the biggest issues that we are facing, not just in Canada but worldwide, is making sure that knowledge is used for the benefit of children. This whole challenge of mobilizing knowledge and getting scientific knowledge use.

I love that word mobilizing knowledge. I think it goes so well with pain and people living well and living beyond their pain. Why is managing children’s pain important for us to put it under the microscope and look at it?

It’s important and we’re increasingly understanding why it’s important with science that shows that it’s not just a nice thing to do. It’s not just something that in the moment is a nice thing to do. That there are many negative, immediate and long-term effects of poorly managed pain early in life. There have been studies showing that poorly managed pain in premature babies in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit is related to changes in the way their brain develops, changes in how they feel pain later in life. Contrary to popular belief where people say, “Pain will toughen you up.” All of the science shows the reverse that when you experienced poorly managed pain, your body becomes sensitized. It experiences more pain later.

We’re understanding a lot more about how poorly managed post-operative pain can contribute to the development of chronic pains. There’s compelling evidence now that there are long-term physiological effects and long-term psychological effects. It’s a dirty little secret people don’t talk about, which is like people don’t like getting needles because they hurt, even adults. One in ten children and adults has a significant fear of needles that interferes with their ability to appropriately seek healthcare. In the context of vaccine hesitancy right now, it’s not the number one reason why people don’t get vaccinated. There are other concerns but it is a barrier. We have evidence-based solutions for managing pain from procedures like vaccinations. There are real significant impacts to not managing pain properly. We have enough science now. We have enough solutions and we should be using them.

It’s so interesting because running into your work has caused me to even reflect on my own. Looking back, I haven’t personally devoted too much attention to pain. Thank you for opening my eyes to that. Why does it not get the attention it deserves, either in healthcare or in the media? People are posting things about opioids and heroin and yet we may be priming the next generation to have more pain than where we are.

It’s always interesting why doesn’t pain get the attention that it deserves? Partly is for a very long time, we just assume and to some degree, a lot of patients still assume that pain is part of healthcare. You’re having surgery, you should have pain. Things that are good for you, interventions, treatment, diagnosis, it’s going to hurt. There’s this belief that’s quite long-standing that’s just part of healthcare and that you’re strong if you can withhold the pain. People will brag to me, “I went for this dental procedure and I told them I didn’t want any analgesia.” I’m like, “That was stupid.” It’s like a badge of honor for people. They don’t know the science that I know that shows that they’re doing long-term damage to their body.

It hasn’t been given a priority in hospitals and we know that there was a study that looked at how much training different types of medical specialists received about pain in a study years ago. There was a study that showed that veterinarians get five times the training in pain than doctors do or physicians, which is crazy. When you think about it, in the animal veterinarian culture, there’s a lot of sensitivity to making sure your pet’s pain is managed. Friends of mine will send me screenshots of posters from waiting rooms and veterinarian clinics that, “We make a commitment to reducing your pet’s pain and providing as much comfort as we can.” It blows my mind that we’ve made those promises to our pets but we haven’t been making those promises to our kids.

I love that because you have parlayed that into, It Doesn’t Have to Hurt, which you’re telling people that we have research that shows we can effectively manage pain throughout the life cycle of a child’s interaction in the healthcare system. You’ve mentioned needles, vaccinations, as kids we’re going to receive needles or kids receive needles for certain interventions. As I went through your website, you have some great stories that quite honestly are quite tear-jerking and very emotional to read them. Some of your work delves into pediatric pain with regard to cancer, where kids are receiving injections or central lines over and over and they’re being exposed to needles. Can you talk a little bit about that work?

There are certain groups of children who are particularly at risk for pain and poorly managed pain. We were funded through the Canadian Cancer Society to do a program specifically focused on raising awareness about the problem of cancer pain in kids. This was very meaningful and important work and we had fantastic partners in this work. In oncology, they have been leaders in advancing procedure pain management. Many of these children have to come back for repeated procedures. If you’re working with kids who need to come back for repeated procedures, you learn very quickly. If you do a bad job at managing one of them, your job next time becomes a million times harder. I often say in the healthcare setting, we often just think about getting through this one procedure. We don’t think nearly enough about what impact how we manage this one is going to have on whether that child ever comes back or who’s going to have to manage that next time. Kids cancer pain has been an area that we’ve been particularly interested in.

One of my PhD students, Perri, did some research attached to this work. It was interesting for us because we did a survey of the prevalence of pain in pediatric cancer patients who were undergoing active treatments but who were also post-treatment. It surprised us. Perri was shocked to see how many children after treatment were still experiencing significant pain. This has led her to develop a whole research program now on pain in cancer survivors. There’s a whole evolving literature that others are contributing to as well around how children with cancer are at risk for developing a complicated pain syndromes post-treatment. Also, there’s some interesting meaning attached to what happens when you’re a cancer survivor and you have an experience of pain. Is that the sign that a cancer is back? How do children and families deal with that anxiety? It’s a complicated area and one that does need more attention. I’m thrilled to have Perri Tutelman in my lab working in this space.

From that work, because all this great information is on your website at KidsInPain.ca, everyone can check that out. There are a couple of other topics that come up. I want to talk about your work with regard to SKIP. The challenges of parenting a child with chronic pain or a child who has pain.

Parenting is the hardest job in the world when everything goes as it should. When you layer on having a child who has some chronic pain condition or chronic illness, it becomes extraordinarily challenging. Chronic pain is tough for parents because it’s one of those things I joke in parenting that when the right thing to do one day becomes the wrong thing to do another day. Nobody sends you a memo or a courier or an email the day that what you were doing that was good before then starts to become part of the problem. In pain, we know that’s the case. For example, when your child is acutely ill and having significant pain or whatever, the right thing to do is to have them stay home from school and to restrict their activities and to try to figure out what’s going on. The problem is when your child has a chronic pain condition, that approach of keeping them back from activities is not the approach that works in terms of dealing with the pain. The focus then becomes keeping them activated with school, keeping them activated with activities so they don’t get deconditioned. Helping them develop coping strategies, more of a rehab model. For parents, that’s a very tricky space to navigate. There are some fantastic intervention programs that focus on helping to address that with parents.

Bring us modern day to your work with SKIP and tell us what SKIP is about.

SKIP is an exciting new national knowledge mobilization network that we’ve been funded for through the Canadian federal government. It’s a program called Networks of Centres of Excellence. I’m a researcher. I’ve spent my whole life applying for grants and all of these grants have always been to generate new knowledge, which is great. It’s critical. I’m not saying we don’t need more science, we absolutely do. I learned the hard way when I became a parent myself. I have four kids between the ages of eight and thirteen. When we started having medical interactions, I realized that all this evidence that I had spent my whole career contributing to wasn’t being used for the benefit of my own kids. My husband’s an anesthesiologist, so between us, we are an interdisciplinary pain team and we struggled to make sure our kids perceived what I knew to be evidence-based pain management from the literature. SKIP is an evolution of our passionate interest in getting knowledge out to those who need it. Unlike every other grant I’ve applied for, we’re not allowed to do any science. We’re not allowed to generate new knowledge. We’re only allowed to mobilize it.

It’s a partnership program where we are partnered with over 100 organizations. Our key partner is Children’s Healthcare Canada, the not for profit organization that has 48 different health institutions under its umbrella, including all the children’s hospitals in Canada. Our goal over the next four years is to improve pain management in as many of these health institutions as we can. How we’ll be doing that is by mobilizing all these evidence-based solutions we have and partnering with different types of people at all levels in all organizations. For example, we’re going to be creating a new hospital accreditation standard for pediatric pain management that will be embedded and integrated into the accreditation process for Canadian hospitals. That’s the top down strategy.

We’ll also be working from the bottom up, making sure that patients and parents have the tools they need. We’ll be building on our parent-based It Doesn’t Have to Hurt initiative arming parents with information. We have a partnership with a group called The Rounds who run essentially a Facebook for doctors. They have a large capture of family physicians and other types of physicians that will be working with them to provide virtual education. What we’re trying to do is think about who are all the knowledge users in the system who need to be armed with information, clients with children in pain. Our strategic plan involves targeting knowledge mobilization activities to each of those groups. Hopefully, by tackling this problem at all levels, we’ll be able to move the needle to get pain better managed for kids. Another innovative part of what we are doing with SKIP is that we have a commitment to what is known as patients included, where patients and caregivers are embedded as equal partners in all of our activities. They are involved in management, they are involved in governance, we have parents and former patients on our board of directors. This isn’t just for patients, this is being done with patients, which gives them a lot of power and authenticity.

How much of the initiative is focused on educating practitioners who are in private practice or in any practice?

Health professionals, practitioners are important part of what we’re doing. I would say they’re one of about five or six different knowledge user groups that we’re targeting. They’re important but we’re also targeting policymakers, administrators, patients and caregivers themselves, and the public at large, trying to raise awareness about the problem of pain and creating a sense of urgency. We think of all of these pieces work together, change is most likely to happen. I have been a passionate believer in the power of patience and the power of parents with our It Doesn’t Have to Hurt Initiative where we were targeting specifically with information about children’s pain. I’m using blog posts than other types of social and digital media. It was interesting because we saw the power of how empowering parents can impact health professionals. One parent shared with us in our evaluation of our initiative that she’d gone into the emergency department, her baby needed an IV. She said to the resident, “I want to breastfeed my baby during the procedure because I’ve heard that it doesn’t have to hurt. This is breastfeeding and needles is an evidence-based pain strategy.” Initially the resident was like, “No, we don’t do that here.”

Certainly, we’ve heard lots of barriers that health professionals put up around this like, “Your baby will choke, your baby will associate breastfeeding with pain,” and there’s no evidence to support any of that. This mother, who had followed our initiatives and felt well-informed, insisted and said, “I want to do this.” The resident went and talked to someone and came back and was told, “Go ahead, let her do it.” She breastfed the baby during the procedure. At the end of the procedure, the residents said, “That was the best procedure I’d ever done. I’m going to recommend breastfeeding for IV insertion to all of my patients from now on who are breastfeeding.” I love that story because maybe he had a lecture about this in medical school, but probably not. Maybe he might go to a workshop or hear it by the conference, but what was most impactful for this health professional was seeing it happen. It probably changed how he’s going to practice from now on. Just one parent. It’s amazing.

What I love about your work is you’re 100% right. We have so much information already. If you go into PubMed, you can spend literally years in there learning about pain, the research that has been done on pain, but we have yet to translate it into practice. How many years does it typically take for us to translate knowledge into clinical practice?

There are various estimates that people have put forward. The most consistent one is that it takes on average seventeen years for the results of research to trickle their way to the front lines. That’s an incredibly long time. I often say to people, for those of us in pediatrics, that’s an entire childhood, a whole generation of kids who miss out on the science that we already have. For me, I’ve been doing this since I was eighteen and I’m 44 now. This means that it’s taken over two decades where the results of some of my research to impact people. It’s a leaky pipeline too. Only about 14% of clinical research ever finds its way to the front line. We have a big problem here and I think the general public is shocked when they hear this. They assume that when a scientific discovery is made, that it’s automatically mobilized and integrated. Science isn’t set up that way, sadly.

I think it’s so important and I talk about that all the time. People say, “Why do you do this?” I’m like, “Because there are brilliant people out there that are doing research that most people never hear about it. It doesn’t get integrated into, into our daily practice.” What are some of the challenges that you might come up against as you begin to roll this project out and disseminate some of this research across Canada? Canada is a big country and there are even multiple systems embedded within Canada. Have you tried to foresee some of what might be down the road?

It is a big country and our health system, there’s a national component to it but most of our healthcare is managed at a provincial level. You have different provinces with different approaches and different health institutions, different cultures, different priorities. This is something that has begun to be better understood around the role of these types of individual contextual environmental types of factors that impact documentation. One of the things that we built into our application was it’s not just enough to disseminate information and to put tools out there or to let people know what they should be doing and what they could use to do it. There needs to be a human factor when it comes to promoting changes in practice. What we built into our proposal and into SKIP was this whole idea of needing human beings as catalysts for uptake and change of practice. We have what are called knowledge brokers that we’re hiring regionally across all of our hubs who will be assigned to support different health institutions. Their job is to develop relationships with the different champions and sites to figure out what they need and how it can be modified and what their unique issues are and also to help move people along. Some organizations are further along in terms of readiness to change than others.

Where do we focus our efforts and how do we move those institutions to this is not a priority at all for them? How do we move them just a little further along the path of being ready? The biggest barrier to implementation is often a human factor. I’ve learned so much about the importance of relationships. We don’t talk about this enough. For change to happen, relationships need to be formed and human beings need to do that. Science doesn’t always reward us for taking the time to make these relations. I’ll say it’s taken me over two decades to establish the relationships that I need to mobilize my knowledge. We need to create these hubs and platforms to make it easier. That’s what we’re doing with SKIP. All the new young scientists who are publishing great work, they shouldn’t have to wait for twenty years to be at a point in their career where they can establish these relationships and move forward. Those are some of the barriers and I’m sure there will be many more along the way that we have yet to even think of. We’ve tried to anticipate what some of the critical ones could be.

When I look at your work, it reminds me a little bit of Lorimer Moseley’s work with pain revolution. When I looked at it, I was like, “This is like a pediatric pain revolution out in here.” It’s cool. Pain education is something that we need to spread globally. When I look at your work, I’m like, “I feel this could potentially be a model that other countries start to look at and move toward.” Have you had any interest from other countries about your work and what’s happening?

We funded through a national knowledge mobilization program. We have definitely had our eye to a potential global international impact. We were able to secure a number of international partners for our applications. The International Association for the Study of Pains in childhood special interest group. It’s funny you had mentioned Lorimer. The Australian Pain Society has been incredibly supportive and a big part of our efforts. We have the Nordic Pain in Early Life group part of our work. We started to lay the groundwork for these types of relationships. We do feel our model has huge potential to scale up globally. Also, we think this partner to approach to knowledge mobilization has a lot of potential in other health areas. Pediatric pain is not the only area where we have this knowledge mobilization crisis. We’re keen to work with other people who may be in a completely different health area but who could potentially learn from what we’re doing around children’s sleep or children’s behavior. Even in the adult as well.

There are so many overlaps with pediatric pain to me. There’s pediatric obesity and pediatric mental health conditions that are on the rise. There are so many great avenues for this work to grow and spread its wings. It’s exciting. What would you recommend to a parent who potentially sees that their child maybe is developing chronic pain or has challenges when they go to the physician’s office? Are there ways for a parent to interact with a professional who may not be as up to date on the type of evidence that you and SKIP is spreading around?

We’re hoping that we will be able to empower parents to feel comfortable to be able to bring evidence word in ways that are accessible for their physician or other healthcare providers. It’s a tricky conversation. There are huge hierarchies in medicine and healthcare. Patients are extremely vulnerable. You sometimes hear stories of patients who are mocked when they bring in information and the doctor is like, “I’m the doctor.” We appreciate that we need to change the system so that patients don’t get put in a situation where they are feeling like they can’t advocate for the care they want. I tell parents all the time that whether you’re having a procedure or your child’s having surgery, just ask a simple question and get people to stop and think. The question is, “What are we going to do about my child’s pain?” It sets an expectation. It’s not, “Are we going to do something about myself?” It’s like, “What are we going to do to manage my child’s pain?” Sometimes that’s enough of a prompt to get somebody to think differently around, “What could we do here? We think this needs to be done quickly, but could we use the topical anesthetic and take the time necessary?” I do say to parents, “Don’t be afraid to ask that.” I have asked it in many occasions like, “Hold on, people. What are we going to do about my child’s pain?”

This is another topic. I don’t know if you’re doing this type of research and if you’ve included this in SKIP at all. Children of parents with chronic pain, so kids that may not have chronic pain themselves, but their parents do have chronic pain. They’re exposed to a context of living with chronic pain in some way in their home.

This is something that’s a big interest for us and we’ve done some work in. I did an early study a couple of years ago with one of my first honor student in Vancouver on this topic. Kristen Higgins, who is a PhD student in my lab who has just defended her dissertation. Her whole dissertation was focused on active parent chronic pain on kids. We published a review in pain a couple of years ago. Indeed, the review of existing studies showed that these children are highly at risk for a whole host of pain problems, as well as behavioral and emotional challenges as well. For Kristen’s dissertation, she ran an impressive lab-based study where she recruited 70 parents who had chronic pain and their kids to come into the lab and she did some lab-based Cold Pressor testing and studied reactions and responses and questionnaires and so on.

We’ve run thousands of kids through research studies in my lab over the years. Some very challenging patient populations like cancer and other chronic illnesses and inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis. I’m always on call when we have kids in the lab because you never know what’s going to happen. Sometimes challenging situations arise. It’s rare that I get a call. When Kristen was running her study, it was basically like one out of every four or five participants, there was some very challenging issue around mental health or pain or suicidality or some child protection issue. We couldn’t believe it. We had never had this frequency of challenges and certainly her study results supported that this is a group that is highly at risk. Also, it was interesting because when we’re running kids from other clinics or patient population, I know who to follow up with.

I follow up with their oncologist or I follow up with their rheumatologists. In this case, it wasn’t the kids who were the patients, it was the parents. These kids were not necessarily plugged into any healthcare provider. They weren’t on anyone’s radar. When we would connect with the adult pain clinicians who were the clinicians caring for the parent and say, “Are you aware?” They’re like, “We never talk to our patients about what’s going on with their kids.” This is a huge gap in terms of our understanding of what we need to do to prevent and treat this population of kids who are at risk. There are some other people who have done good work in this space, like Anna Wilson and Amanda Stone. We’re at a point now where we need to develop and evaluate and implement some robust intervention and prevention programs for children whose parents have chronic pain.

It brings in a little bit of the primary care aspect into it. This can probably go two ways. It can be screened when the adult goes to let’s say primary care or the “pain doctor” or when the child is going for their annual pediatric visit to start to screen for these types of, “What’s happening in the home? How is everything at home? Is it having an impact on your child?” We can start to slow down this progression that happens. Can you share with us maybe one or two success stories that when you look back, you’re like, “My work came to life in this particular?” You gave us one case with the breastfeeding, but is there anything else come to mind?

There were so many amazing things that happened as part of our It Doesn’t Have to Hurt project and certainly now as Solutions for Kids In Pain. I’ll share with you one from each of those initiatives. First one, It Doesn’t Have to Hurt. One of the things that we built into our social media initiative was an opportunity to have Twitter parties or Twitter chats where parents could come online at an advertised time and use our #ItDoesntHaveToHurt. We brought the scientists online too. They could ask questions around things they’d heard and were wondering about. There was real live engagement between scientists and parents, which was amazing. It was funny because Twitter Canada saw what we were doing and how we were using their platform to spread the word and they invited us to do one of our virtual Twitter parties from their headquarters in Toronto. We brought our whole It Doesn’t Have to Hurt team together and it had been a completely virtual project. All the people who’d been working on it, I’d never met.

We were able to get some special funding to bring everybody together. Not only did we have an actual Twitter party at Twitter Canada, but the most important part of what they did was they allowed us to use their proprietary video Q&A app that they’ve only enabled for celebrities and politicians. Not only we could we answer parents’ questions by typing, we were able to videotape our answers and answer a parent’s questions that way. The engagement we had on that particular evening was huge. It was amazing to see Canadian parents reaching out. We’re able to answer their questions and talk about shrinking that seventeen-year gap. It’s spontaneous interaction and parents sharing information with one another. From that perspective, that was a real success story in terms of having a lot more visibility for children’s pain. It’s like a niche issue. The fact that a major social media company would open its doors and allow us to use its platform in this way was exciting.

With Solutions for Kids In Pain, we’re just getting started. Already there have been so many things that have been exciting. I will say probably the most exciting moment so far for our team was being invited to be guests of one of the senators in the Senate of Canada, Senator Colin Deacon in Ottawa. He has been following our work before he was even a senator. He was impressed by the public-private partnership that we had developed for It Doesn’t Have to Hurt and the extended Solutions for Kids In Pain. He invited our group to Ottawa. We had individual meetings. We had basically a lobby day where we had members of our team, including patients and caregivers, meet with MPs and senators and spread the word. He invited us all into the Senate when he was sitting in and made a speech about what we were doing and why this partnered approach to knowledge mobilization is so effective. It was an inspiring moment. I’m excited about the potential that we have here with this four-year grant to make a difference for kids in pain.

The work between the grants you have going on and the social media work you’ve done, and all the research you had that backs that up. You have a wonderful mix of things that are happening. I’m excited to watch your work and see how it develops and please keep in touch with us. Let everyone know how they can learn more about you, all your information, your websites and everything.

For our Solutions for Kids In Pain or SKIP initiative, you can come to www.KidsInPain.ca. We also are active on all social channels, @KidsInPain. You can find me on Twitter, @DrCChambers and we also have a website, ItDoesntHaveToHurt.ca. We use the #ItDoesntHaveToHurt to tweet about anything related to children’s pain. If ever you want to join in on a conversation online, feel free to do so. I want to thank you, Joe, for the knowledge mobilization you’re doing, putting yourself out there, creating this show that has a tremendous reach. It’s such a critical part of helping to shrink this gap between science and practice. Thank you.

Thank you. I could not do this without people who care about pain, researchers, practitioners, people just like Dr. Christine Chambers. Make sure you check out KidsInPain.ca. You can tweet or check out @KidsInPain and #ItDoesntHaveToHurt. If you know practitioners, physical therapists, mental health professionals, other professionals who are interested in kids in pain, share this information with them. Share this information on Facebook, on Twitter, throw it into a Facebook group where people are talking about kids in pain. This work is special and I’m so happy to be sharing this. On behalf of Dr. Christine and myself, I’ll see you again soon.

Important Links:

- Dr. Christine. Chambers

- It Doesn’t Have to Hurt

- International Association for the Study of Pain

- North American Pain School

- Solutions for Kids In Pain

- Patrick McGrath

- Canadian Cancer Society

- Perri Tutelman

- KidsInPain.ca

- Networks of Centres of Excellence

- Children’s Healthcare Canada

- The Rounds

- PubMed

- Australian Pain Society

- #ItDoesntHaveToHurt Twitter Initiative

- www.KidsInPain.ca

- @KidsInPain on Twitter

- @DrCChambers on Twitter

- ItDoesntHaveToHurt.ca

- @KidsInPain on Facebook

- https://www.YouTube.com/watch?time_continue=14&v=_xOJQaFuJDk

About Christine Chambers, PhD

Dr. Christine Chambers is the Canada Research Chair (Tier 1) in Children’s Pain and a Killam Professor in the Departments of Pediatrics and Psychology & Neuroscience at Dalhousie University. She is based in the Centre for Pediatric Pain Research. Dr. Chambers is a clinical psychologist whose research is aimed at improving the assessment and management of children’s pain. She has published over 150 articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals and was identified as one of the top 10 most productive women clinical psychology professors in Canada.

Dr. Christine Chambers is the Canada Research Chair (Tier 1) in Children’s Pain and a Killam Professor in the Departments of Pediatrics and Psychology & Neuroscience at Dalhousie University. She is based in the Centre for Pediatric Pain Research. Dr. Chambers is a clinical psychologist whose research is aimed at improving the assessment and management of children’s pain. She has published over 150 articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals and was identified as one of the top 10 most productive women clinical psychology professors in Canada.

Her Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) funded “It Doesn’t Have to Hurt” initiative for parents generated 150M content views worldwide, trended nationally on social media several times, won multiple national and international awards, and was featured in The New York Times, The Globe & Mail, and on CBC’s The National. Dr. Chambers holds leadership roles in the International Association for the Study of Pain and the North American Pain School and is a member of the CIHR Institute Advisory Board on Musculoskeletal Health and Arthritis.

A leader in patient engagement and knowledge mobilization, Dr. Chambers has given numerous public presentations including a TEDx talk. She is the Scientific Director of a recently established $7.3M national Networks of Centres of Excellence Canada knowledge mobilization initiative with over 100 partners, Solutions for Kids in Pain/Solutions pour la douleur chez les enfants (SKIP). Headquartered at Dalhousie, SKIP’s mission is to improve children’s pain management by mobilizing evidence-based solutions through coordination and collaboration.

The Healing Pain Podcast brings together top minds from the world of pain science and related fields to discuss the latest findings and share effective solutions for persistent pain.

If you would like to appear as an expert speaker in an episode of The Healing Pain Podcast contact [email protected].

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join the Healing Pain Podcast Community today: