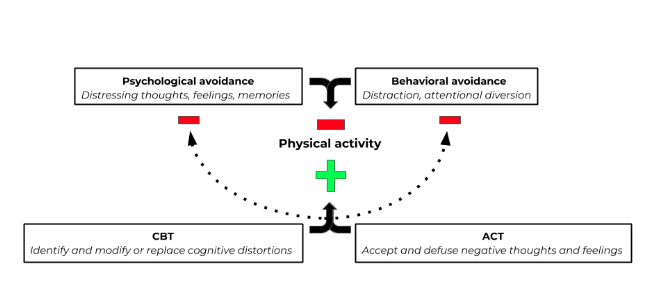

The benefits of regular physical activity and exercise are numerous, but for many people, being physically active and engaging in regular exercise can be difficult. This difficulty, especially for those living with pain, can be related to the sometimes unpleasant sensations associated with physical activity. Struggling with unpleasant bodily sensations can in turn lead to psychological distress including fear, anxiety and avoidance.

If not properly addressed, these feelings of distress and discomfort may lead to what is known in the ACT model as ‘experiential avoidance’. Experiential avoidance results when one avoids unpleasant thoughts, feelings, memories, physical sensations, and other internal experiences, even when doing so causes harm in the long-run, or opposes one’s life values (1).

Two Mainstream Psychological Approaches to Promote Physical Activity

Experiential avoidance is defined by psychological and behavioral evasive strategies; these can variably serve to restrain physical activity, but also to impair and delay recovery from behavioral disorders and clinical conditions, including chronic pain (2, 3).

So how can physical therapists address their clients’ aversion to physical activity, movement or exercise?

While diverse behavior modification strategies can reduce psychological barriers to exercise, the short-term effects are usually modest, and change is not maintained (4). Interestingly, studies showed that ongoing professional support of self-directed physical activity significantly enhances the effects of these interventions (5). This evidence emphasizes the importance of integrating cognitive-behavioral approaches into physical therapy practice.

Check out my blog: 7 COGNITIVE-BEHAVIORAL SKILLS EVERY PHYSICAL THERAPIST CAN USE

Two psychotherapeutic strategies, Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), have shown efficacy in tackling experiential avoidance and helping to promote physical activity.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been used for almost 60 years to foster adaptive behavior in a wide range of psychological and clinical conditions. CBT seeks to identify, challenge, and modify or replace negative or irrational thoughts (cognitive distortions) to promote behavior change.While CBT has been successful in many interventions (check out Top 3 Methods to Target Pain Catastrophizing) evidence suggests that efforts to directly control internal experiences are often ineffective (6, 7 8). This is because our capacity for self-control is limited, and that overdoing it may actually impair our ability to override unhelpful thoughts, emotions, urges, and behaviors (9).

Given these caveats, strategies that focus on boosting acceptance and willingness to experience some discomfort might provide the greatest health benefits.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is a different approach to behavior change based on:

- Acceptance -rather than avoidance- of negative thoughts and feelings

- Openness – that these thoughts and feelings are mere psychological constructs and do not represent one’s “truth”; and

- Engagement – a commitment to productive behavior to pursue meaningful values and goals.

Using ACT to Motivate and Promote Exercise

In a previous blog (Using ACT to Promote Physical Activity in Sedentary Adults) we reviewed a study that showed how ACT could help physically inactive people overcome experiential avoidance related to physical activity and exercise. While there still are no studies directly comparing the efficacy of CBT vs ACT in relation to physical activity promotion, Drexel University researchers at the Dept. of Psychology showed that a brief ACT intervention can also increase physical activity levels in young women.

The 2011 study involved women (18-35 years old) enrolled at Drexel University in Philadelphia, PA, who wanted to increase their physical activity, but who were concerned that doing so would be difficult. To be part of the study, they could not be a member of a varsity or club sport team, and had to be able to safely engage in physical activity (10). Participants were randomly assigned to two groups, and attended two, two hour intervention sessions, held two weeks apart (on weeks two and four) over the eight-week study period:

The education intervention (n = 19) was based on the American College of Sports Medicine guidelines and provided information regarding:

- Safely engaging in physical activity

- Benefits of flexibility, strength, and aerobic activity and best ways to add these into workouts

- How to measure improvement in physical activity

- Injury prevention, appropriate nutrition for physical activity, and exercise attire and footwear

The ACT intervention (n = 35) was designed to help participants develop willingness skills, become more mindful, distance themselves from distressing thoughts about exercise, and strengthen their commitment to exercise-related values. It was based on various bibliographical resources (1, 11, 12) teaching participants that:

- Attempts to control distress associated with physical activity (eg, fatigue, physical discomfort, urges to stop) are often counterproductive

- Experiential and metaphorical exercises can maximize engagement and understanding

- Reflecting on the reasons why increasing physical activity is important is beneficial (i.e. improved health, weight management, stress relief, increased energy, etc.)

- Engagement in behaviors that are consistent with their freely chosen, personal life values should be a priority (eg, health)

- Commitment to difficult behavioral goals, and the sometimes unpleasant experiential states they entrail, requires connecting psychologically with life meaningful life values to make such effort and sacrifice worthwhile

What was measured?

Assessments were conducted at baseline (week 1), post-intervention (week 5), and follow-up (week 8) and included:

#1- Number of Athletic Center Visits per week

#2- Mindful Awareness, measured using the Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale (PHLMS), a self-reported measure of mindfulness that evaluates present moment awareness and nonjudgmental acceptance

#3- Defusion From Negative Internal Experiences, assessed using the Drexel Defusion Scale (DDS), a 10-item scale that assesses the degree of psychological distance from various negative thoughts and feelings

#4- Physical Activity Experiential Acceptance, evaluated using the Physical Activity Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (PAAAQ), an 8-item questionnaire that measures the acceptance of internal barriers to exercise

What did the results show?

All baseline measures were similar between groups; however:

- Physical activity (visits to the athletic facility) did not increase after the education-only intervention.

- ACT participants effectively doubled their physical activity from baseline to post-intervention, increasing physical activity from 1 to 2 days per week; this increase remained marginally significant at follow-up, indicating that some of the benefits of the intervention were maintained after the intervention ended.

- DDS scores improved significantly over time in the ACT group, but decreased instead in the Education group. This may indicate that defusion is a particularly effective technique to increase willingness to experience discomfort in brief exercise interventions.

Dr. Tatta’s simple and effective pain assessment tools. Quickly and easily assess pain so you can develop actionable solutions in less time.

Harnessing the Power of ACT in Physical Therapy Practice

The study summarized above provides further evidence of the positive effects of ACT on exercise promotion (13). However, its authors report that “The evidence for (physical activity) maintenance was not as strong for participants who only attended 1 of 2 intervention sessions, which suggests that a minimal dosage may be necessary and that increasing the intensity, length, or frequency of intervention contacts may result in greater maintenance of change”.

This might also suggest that to achieve long-lasting commitment to physical activity and tangible health effects, physical therapists may need to target ACT’s six core processes during a first encounter with their clients or patients, as well as reinforce them over the course of treatment.

Have you tried ACT or other behavioral strategies to improve your clients’ adherence to exercise?

To learn more about ACT for pain, exposure and physical activity visit this page:

REFERENCES:

1- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change. Second Edition. Guilford Press, New York, NY.

2- Kashdan, T. B., Barrios, V., Forsyth, J. P., & Steger, M. F. (2006). Experiential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: Comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behaviour research and therapy, 44(9), 1301-1320.

3- Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., & Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 64(6), 1152.

4- Kahn, E. B., Ramsey, L. T., Brownson, R. C., Heath, G. W., Howze, E. H., Powell, K. E., … & Corso, P. (2002). The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity: a systematic review. American journal of preventive medicine, 22(4), 73-107.

5- Foster, C., Hillsdon, M., Thorogood, M., Kaur, A., & Wedatilake, T. (2005). Interventions for promoting physical activity. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (1), CD003180.

6- Borton, J. L., Markowitz, L. J., & Dieterich, J. (2005). Effects of suppressing negative self–referent thoughts on mood and self–esteem. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(2), 172-190.

7- Marcks, B. A., & Woods, D. W. (2005). A comparison of thought suppression to an acceptance-based technique in the management of personal intrusive thoughts: A controlled evaluation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(4), 433-445.

8- Barraca, J. (2012). «Mental control» from a third-wave behavior therapy perspective.

9- Muraven, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle?. Psychological bulletin, 126(2), 247.

10- Butryn ML, Forman E, Hoffman K, Shaw J, Juarascio A. A pilot study of acceptance and commitment therapy for promotion of physical activity. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2011 May;8(4):516-22.

11- Deci E, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum; 1985.

12- Bach, P., & Hayes, S. C. (2002). The use of acceptance and commitment therapy to prevent the rehospitalization of psychotic patients: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 70(5), 1129.

13- Kangasniemi, A. M., Lappalainen, R., Kankaanpää, A., Tolvanen, A., & Tammelin, T. (2015). Towards a physically more active lifestyle based on one’s own values: the results of a randomized controlled trial among physically inactive adults. BMC public health, 15(1), 260.